|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

4 - The

Land Claims Struggle

|

|

|

Chapter

18 - A Strengthened Case

|

|

Chapter 18

A Strengthened Case

While continuation of the land freeze was not threatened by the Congress, the election of Richard M. Nixon in 1968 did pose a possible threat to it. Once in office, the new president would replace Interior Secretary Udall, who had imposed the land freeze, with a person of his own choosing.

Just before the election, Udall had commented on the importance of the freeze. "Frankly," he said, "I do not believe we would have made any significant progress on the Native claims issue if we had not held everyone's feet to the fire (or perhaps I should say to the ice) with the freeze." Then, before giving up his office he changed the informal freeze into one having the force of law: he signed an executive order continuing the freeze in effect.

Hickel nomination. The man the new president nominated to replace Udall — Alaska Governor Walter Hickel — had spent the last two years trying to have the freeze lifted. Now, having been nominated to the Interior post, he said, "What Udall can do by executive order I can undo."

Cabinet nominees, however, require confirmation by the Senate. Because of the growing importance of the Alaska Federation of Natives, its endorsement was one which Hickel sought. But just as the Federation was important to Hickel, the freeze was important to Natives.

|

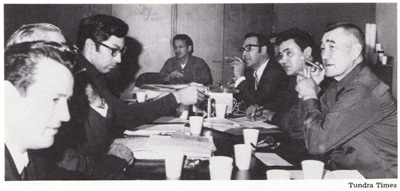

| AFN Board of Directors meeting, 1968. (Left to right) Donald Wright, Frank Degnan, Willie Hensley, Emil Notti, Flore Lekanof, Al Ketzler, and Charles Franz |

The AFN decided to withhold any formal announcement of support or opposition to Hickel until he could explain how he would protect Native land rights. To seek that explanation, a small delegation, headed by Federation president Emil Notti, set out for Washington, D.C. Federation vice-president John Borbridge, Jr., summed up the delegation's views: ". . , the most effective way to safeguard the Native land claims was to secure from Governor Hickel reliable assurance that, as Secretary of the Interior, he would protect the Native-claimed lands from further disposition until Congress had a chance to settle the entire Native land claims question."

The confirmation hearings were very difficult for Hickel. Powerful conservationist groups testified in opposition to his appointment. The Native delegation had obtained support from key senators on the committee, and they sternly questioned the nominee.

AFN victory. Although there was much pressure to endorse, the Native delegation refused to act. Realizing that his nomination was at stake, Hickel finally gave in and promised to extend the land freeze until December of 1970. Based on that commitment, Notti and others of his delegation endorsed his nomination.

|

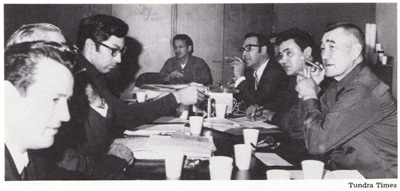

| Emil Notti, president of Alaska Federation of Natives, and John Borbridge, Jr., vice-president, in television interview in Philadelphia |

Winning Hickel's promise was an important victory for Native leaders. At the same time that the freeze protected the land rights of Natives, the freeze made a settlement a matter of concern to the State and to many persons and interests within the state. The victory was important, too, for what it told about the leadership of the AFN: it was independent, increasingly strong, and growing in its ability to influence the processes of government.

A government study. Although new bills had been introduced during 1968 and hearings had been held, none had been acted upon by committees of either house. The chairman of the Senate committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Henry Jackson of Washington, had, however, requested that a program of comprehensive research be carried out as a basis for appropriate legislation. He asked that the study be performed by the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska. This was a small federal agency headed by Joseph H. Fitzgerald, which had been established following the 1964 earthquake to bring about coordinated planning among federal and state agencies.

The document produced in response to the request, Alaska Natives and the Land, was made public in early 1969. Its 565 double-size pages told of present social and economic status of Natives, portrayed historic patterns of settlement and land use, and examined the many elements of land ownership and land claims.

Villagers. Summarizing their findings about the economic and social circumstances of villagers, the authors said:

Urban Natives. Speaking of the Natives who live in the large cities, the authors said:

Because adult Natives are often less well-educated than other adults and lack marketable skills, their rate of joblessness in these communities is higher than among other groups, and those who are jobholders are typically in lower-paying positions. Migrants from villages to urban areas are frequently ill-equipped, by cultural as well as educational background, to make an easy transition to new patterns of life and work, but few communities have begun to provide assistance to them; and the consequences for too many are severe stresses resulting in alcohol problems and other personality disorders.

Land ownership. The research group found Natives to own little land outright:

Alaska Natives who claim two-thirds of the state own in fee simple less than 500 acres and hold in restricted title only an additional 15,000 acres. Some 900 Native families share the use of 4 million acres of land in 23 reserves established for their use and administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. All other rural Native families live on the public domain. And reindeer reserves account for one and a quarter million out of the four million acres of reserved lands. Without government permit, these reindeer lands may only be used for reindeer husbandry and subsistence purposes.

Specific land legislation passed for Alaska Natives — the Alaska Native Allotment Act of 1906 and the Townsite Act of 1926 — has failed to meet the land needs of the Native people.

Valid claims. Of greatest importance, the researchers supported the claims of Natives to having used and occupied most of Alaska:

Aboriginal Alaska Natives made use of all the biological resources of the land, interior and contiguous waters in general balance with its sustained human carrying capacity. This use was only limited in scope and amount by technology.

And further, such claims are "valid," the researchers said, and could properly become subject to compensation.

While the report supported Native claims to most of Alaska, and suggested that 60 million acres would be required for subsistence, its accompanying recommendations for settlement included only seven to ten million acres of land that would be owned by Natives. Other lands would be available for use by Natives, however.

Mineral revenues. Recommendations of the Federal Field Committee helped to revive the idea of looking to future revenues from minerals as a means of compensating Natives for lands claimed, but not transferred to them. The AFN had proposed sharing in mineral revenues in its second bill, but because of opposition to its specific proposal, had discarded it in favor of a $500 million appropriation as compensation.

The Field Committee's recommendations, which became the basis of a bill introduced by Senator Jackson, also raised the possible compensation to one billion dollars, the highest of any proposal to date. Of this amount only $100 million would be appropriated. The remainder was to come from a limited share of revenues derived from minerals and other resources of federal lands.

Support of the concept of revenue-sharing by Jackson brought back unlimited revenue sharing as a feature in the AFN proposal for settlement adopted in May of 1969. The AFN board reaffirmed its position that the land settlement should be 40 million acres, the appropriation $500 million, and that Native corporations be the instruments of settlement at the village, regional, and state levels. In addition, the board called for a two-percent perpetual share of the revenues produced from lands given up by Natives to the State in the settlement.

AFN president Emil Notti defended the principle of revenue-sharing by pointing out that a fair settlement of Native claims was surely related to the fair value of lands being given up. And the value of such lands was yet to be determined. With an eye on the State's upcoming North Slope oil lease sale, Notti said if the State were to get one to two billion dollars from oil companies for leases to several hundred thousand acres, too small a cash settlement for Natives would be like the sale of Manhattan Island by the Indians.

Oil lease sale. Later in the year, the value of oil to the State of Alaska — and perhaps to Native land claimants — was made clear by the State's oil lease sale. For the right to oil acreage in the Prudhoe Bay region, oil companies paid over $900 million to the State of Alaska.

One who attended the sale, Tundra Times staff writer Thomas Richards, Jr., described the event:

Inside the Sidney Laurence Auditorium, the governor of the State of Alaska, said, 'Let us manage our birthright.'

Meanwhile [outside the auditorium], a handful of young Natives picketed and distributed leaflets under the watchful eyes of police.

Organized by Native land rights advocate Charlie Edwardsen, the young Eskimo and Indian protestors quietly proclaimed, 'We are once again being cheated and robbed of our lands.'

What the oil sale showed was that, if the State could sell leases on small tracts of land for so much money, Natives were not asking for too much in seeking a similar amount of money for the surrender of millions of acres. As AFN first vice-president John Borbridge, Jr., observed: The sale "will clearly demonstrate that the demands of the Natives are not out of line."

The sale also showed Congress that the State could afford to share some of its mineral revenues with Native people by way of compensating them for land claims surrendered.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |