|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

4 - The

Land Claims Struggle

|

|

|

Chapter

14 - New Threats to Land Rights

|

|

THE LAND CLAIMS STRUGGLE

"A controversy of immense proportions is rapidly coming to a head in Alaska. It is a situation which has lain dormant (except for sporadic outbursts) since Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867. This problem has been skirted by Congress, alternately grappled with by the Department of the Interior then dropped to allow the furor to settle, kept Alaskan political leaders frustrated, and the courts have ruled time and again — but never with finality or clarity. The problem is simply this: What are the rights of the Alaskan Natives to the property and resources upon which they have lived since time immemorial?"

—William L. Hensley (Igagruk)

"What Rights to Land Have

the Alaska Natives?" (1966)

In 1960 Alaska Natives made up about one-fifth of the state's population. Although they were a minority of the total, most Natives lived where they were a majority — in perhaps 200 villages and settlements widely scattered across rural Alaska. Most of the white population lived in a half-dozen cities, principally in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, and Ketchikan.

Living away from these urban centers, most Natives could use the land as they and their ancestors had for thousands of years. Continued use seemed a certainty.

But the decade of the 1960's was to be marked by the emergence of new threats to Native land rights. In response, Natives formed local and regional organizations to preserve their rights and their lands. Communication among widely separated villagers was improved as a Native newspaper was founded and as government programs began to bring Natives together in planning for the programs affecting their lives. After several unsuccessful attempts, Natives organized in the second half of the decade into a statewide organization.

By this time, claims of Natives to lands traditionally used were being officially recorded. Protests against the transfer of land ownership to others were mounting. There came to be a growing recognition among political leaders in the state and the nation's capital that solving the problem of Native claims was required, partly because the claims were just, and partly because the future of the state itself was tied to finding a solution to the claims.

What began in 1961 as an effort by Natives to preserve their land rights against others was to be concluded with a settlement of Native land claims in 1971 by the Congress.

Chapter 14

New Threats to Land Rights

Project Chariot. The first organized efforts of the 1960's to preserve ancient land rights had their beginnings in the proposed use of atomic-age technology. These efforts began in northern Alaska.

When Inupiat Eskimo artist Howard Rock traveled from Seattle to visit his birthplace at the village of Point Hope in 1961, he learned that the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission was planning to set off a nuclear device at nearby Cape Thompson. The experiment, which was called Project Chariot, had brought scientists and engineers into the region to plan for the use of the atomic explosive to create a harbor where none had existed before. The facility was expected to be used eventually for shipment of minerals and other resources from the northwest coast.

Residents of Point Hope, Kivalina, and Noatak worried about the potential danger of radioactive contamination to themselves and to the animals which they hunted for their livelihood. Rock, who soon found himself the spokesman for Point Hope, expressed concern over the failure of the commission to think of the safety and welfare of the people of the Cape Thompson area. "They did not even make a tiny effort," he said, "to consult the Natives who lived close by and who have always used Cape Thompson as a hunting and egging area."

Despite assurances from the federal agency that Project Chariot would be beneficial to the Eskimos of the region and to all of mankind, northwest villagers remained strongly opposed to it.

|

SELECTED DATES |

|

|

1961 |

State land selections threaten continued use of lands in Minto area. |

|

1961 |

Inupiat Paitot meets to discuss protection of aboriginal rights. |

|

1962 |

"Tundra Times" is established. |

|

1963 |

Proposed Rampart Dam protested by Stevens Village and other Yukon River villages. Alaska Task Force calls upon Congress to define Native land rights. |

|

1966 |

Statewide conference leads to organization of Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN). Interior Secretary Stewart Udall imposes a "land freeze" to protect Native use and occupancy. |

|

1967 |

First bills introduced in Congress to settle Native land claims. Native protests and claims to land reach 380 million acres. |

|

1968 |

Alaska Land Claims Task Force, established by Governor Hickel, recommends 40 million-acre land settlement. Governmental study effort (Alaska Natives and The Land) asserts Native land claims to be valid. |

|

1969 |

North Slope oil lease auction produces $900 million for the State of Alaska. |

|

1970 |

A land claims bill is passed by the Senate, but Natives are disappointed in its land provisions. |

|

1971 |

Bills pass both houses of Congress, but differences in them require conference committee; its compromise version passes both houses. Following acceptance by the AFN convention, President Nixon signs the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (P.L. 92-203) on December 18. |

|

| The hunter |

Hunting rights. The strong feeling against Project Chariot in the northwest was matched in Barrow in the outrage felt by other Inupiat Eskimos over limitations being imposed upon their age-old practice of hunting ducks for subsistence at any time of the year.

The hunting rights issue had its beginnings in 1960 when State Representative John Nusungingya was arrested for shooting ducks outside of a hunting season established by an international migratory birds treaty. Two days after he was arrested, 138 other men shot ducks and presented themselves to federal game wardens for arrest. By 1961, the charges against all of them had been dropped, but all Natives were warned that future violations would result in arrest and prosecution.

|

| First president of Inupiat Paitot, Guy Okakok of Barrow |

Inupiat Paitot. To resolve these issues, northern Eskimos enlisted the support of the Association on American Indian Affairs, a private, charitable organization based in New York City, and held a conference in Barrow in November of 1961. Neither issue was immediately settled, but the conference did win the attention of high officials of the U.S. Department of the Interior. And it led to the development of the first regional Native organization to be established since the founding of the Alaska Native Brotherhood nearly a half century earlier. The new organization, Inupiat Paitot (the People's Heritage), chose Guy Okakok of Barrow as president.

A second meeting of Inupiat Paitot, also assisted by the Association, was held in late 1962 in Kotzebue. Twenty-eight delegates from villages as widely separated as Kaktovik on Barter Island and Stebbins on Norton Sound attended. They discussed their need for more schools, employment opportunities, and adequate housing, but they gave their major attention to the problem of growing threats to the continuation of their food-gathering way of life.

Delegates learned at the conference that there was little promise in the one way open to them to obtain legal ownership of land. Although the Native Allotment Act allowed a person to obtain title to 160 acres of land if he could demonstrate use and occupancy over a five-year period, there was a barrier to doing so. The Bureau of Land Management, the federal agency having custody of the public domain, had rejected hunting and fishing activities as proof of use and occupancy under the act. Partly for this reason, only 101 allotments had been made in Alaska in the 56 years since the act had been adopted by Congress.

A guest of honor at this meeting was Alfred Ketzler, an Athabascan Indian from Nenana. Ketzler was chairman of Dena Nena Henash (Our Land Speaks), an association which had been organized earlier in 1962 to deal with land rights and other problems. One of the results of its meetings, he explained, was that "our people learned that almost every village faces the same problems: mainly land and hunting rights; jobs and village economy."

Ketzler was among the first to propose Congressional action to preserve land rights, instead of court action. He said:

Your grandfathers and mine, left this land to us in the only kind of deed they knew . . : by word of mouth and our continued possession. Among our people this deed was honored just as much as if it was written and signed by the President of the United States. Until recent years, a man's honor was the only deed necessary. Now, things have changed. We need a legal title to our land if we are to hold it. Our right to inherit land from our fathers cannot be settled in court. It is specifically stated in early laws that Congress is to do this by defining the way which we can acquire title. We must ask Congress to do this.

Tundra Times. By the time the second Inupiat Paitot meeting was held, at least one recommendation of the first — "that a bulletin or newsletter be published and circulated" — had been fully realized. The first issue of the Tundra Times was published on October 1, 1962.

|

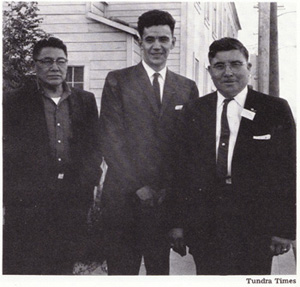

| Howard Rock, Al Ketzler, and Al Widmark, 1964 |

The editor of the paper was Howard Rock, who had helped organize Inupiat Paitot and who had been urged by villagers to begin the newsletter. His assistant was a Fairbanks reporter who had covered the Barrow meeting, Tom Snapp. Financial support had been provided by Dr. Henry Forbes, a Massachusetts physician who was chairman of the Alaska Committee for the Association on American Indian Affairs.

|

| Dr. Henry S. Forbes, benefactor of the Tundra Times |

In its first issue, the editor told of two purposes. It would be a means of reporting the policies and goals of the Native organizations, and it would become a source of information on Native issues. The first Tundra Times editorial announced:

Natives of Alaska, the Tundra Times is your paper. It is here to express your ideas, your thoughts and opinions on issues that vitally affect you . . . With this humble beginning we hope, not for any distinction, but to serve with dedication the truthful presentation of Native problems, issues, and interests.

The Tundra Times did not have to look very hard to find issues. Many problems, largely ignored by other newspapers, existed in the Native communities — inadequate educational programs, poor health care, substandard housing conditions, incidents of discrimination, and the lack of employment opportunities for Natives.

The appearance of the Tundra Times gave Alaska Natives a common voice for the first time. It was to explore a variety of issues, but its impact was to be most far-reaching in the attention it gave to land rights of Eskimos, Indians, and Aleuts.

State land selections. The greatest threat to their land rights during the early 1960's came about because of the Alaska Statehood Act. While the act recognized the right of Natives to lands which they used and occupied, it did not provide any means of assuring such use and occupancy. And by authorizing the new State government to select and obtain title to 103 million acres of land from the public domain, the continued use of lands by Natives was endangered.

One of the areas where state land selections first conflicted with Native hunting, fishing, and trapping activities was in the Minto Lakes region of Interior Alaska. The State wanted to establish a recreation area in 1961 near the Athabascan village of Minto and to construct a road so that the region would be more easily accessible to Fairbanks residents and visiting sportsmen. In addition, State officials believed that the area held potential for future development of oil and other resources. Learning of these plans of the State, the village of Minto had filed a protest with the U.S. Interior Department. They asked the federal agency to protect their rights to the region by turning down the State's application for the land.

In response to the protest, a meeting of sportsmen, biologists, conservationists, and State officials was held in 1963 to discuss the proposed road and recreation area. The chief of Minto, Richard Frank, told the group why they had filed a protest:.

Now I don't want to sound like I really hate you people, no. If we were convinced that everyone would benefit, that the people of Minto would benefit, we might go along. The attitude down there is that you people were going to put a road into Minto Lakes without even consulting the people who live there, who hunt and fish there, who use the area for a livelihood! If you people could live off Minto Flats for one year or even a quarter of a year, you would understand my point.

Frank argued that State development in the region would ruin the subsistence way of life of the Natives and urged that the recreation area be established elsewhere, where new hunting pressure would not threaten the traditional economy. He said, "A village is at stake. Ask yourself this question, is a recreation area worth the future of a village?"

Many others from villages throughout Alaska began to ask similar questions about the danger which State selections presented to their land rights. Leaders such as Ketzler and Rock, accompanied by representatives from the Association on American Indian Affairs, traveled to villages urging them to act to protect their lands from encroachment. They warned them that, unless they filed their claims and protests with the Interior Department, lands they considered theirs would soon end up as the property of the State or others.

In early 1963, about one thousand Natives from 24 villages sent a petition to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall requesting that he impose a "land freeze" to stop all transfers of land ownership for the areas surrounding these villages until Native land rights could be confirmed. The petitioners came from the Yukon River delta, the Bristol Bay area, the Aleutian Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula. No action was taken by the Interior Department in response to the petition.

Rampart Dam. Another kind of threat to lands used by Natives during this period was federal withdrawal of lands from the public domain, especially withdrawals like one for the proposed Rampart Dam. The federal project, planned to produce electric power and to create a recreation area, would have flooded numerous villages and vast land areas traditionally used by Athabascan groups.

When Allen John, a resident of Stevens Village, was informed of the proposal, he had this reaction: "We are concerned about the Rampart Dam at which the white man are gonna put in down below us. The project will ruin our hunting, trapping and fishing on which we have lived for so many years . : . What are we supposed to do, drown or something?"

|

A combination of the threat of impending State land selections and the proposed dam prompted Stevens Village to file a protest during June of 1963. In a letter accompanying the claim, the Stevens Village Council explained why they wanted to obtain title to an area of more than a million acres. The Council wrote, "We use an area of 1,648 square miles for hunting, fishing, and for running our traplines. This is the way in which our fathers and forefathers made their living, and we of this generation follow the same plan."

Three months later the villages of Beaver, Birch Creek, and Canyon Village also filed claims to land. But there was to be no resolution to their claims, or the claims of other villages, for eight more years.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |