The People

History

Available evidence indicates that man first arrived in Alaska crossing a land bridge in the region now occupied by waters of the northern Bering Sea, Bering Strait, and the Chukchi Sea. The land bridge existed for thousands of years and its human occupancy was at least partly motivated by the presence of game animals and other resources attractive to nomadic hunters. Over many successive generations, people of Asiatic origin moved eastward into new hunting areas, reached the Alaska mainland, and settled or moved on.

| Mrs. Maria Ayuluk of Chevak, Alaska |

|

Some groups of these early migrants remained in areas now geographically associated

with the Bering and Chukchi Sea coasts and gradually spread north and south,

across the Arctic into Canada, Labrador, and Greenland. These permanent settlers

of the coastal margins were the ancestors of the Yupik and lnuit Eskimo. Other

groups spread along the coastlines and discovered routes to the Interior where

they encountered natural systems different from those of the coastal areas.

These interior settlers were the ancestors of the Athapascan Indians and other

North American Indian groups (Figure 187).

Figure 186 Historical Patterns of the Yukon Region (1.2MB) Oversize Document may take some time to load

Indian legends tell of migrations when distant ancestors on a continent to the west fled before the onslaughts of more warlike tribes to the safety of "Al-ay-ek-sa," the Great Land. There they discovered the "Kwikpak," or "mighty river," the ancient name of the Yukon River. To early Indians the Kwikpak was not just the mighty river, it was the river of all rivers; the essential thread holding the world together; heaven was at its headwaters, all humanity along its course, and where the river ended so did the earth.

The Yukon and its tributaries provided access and means for travel and communication and trade between peoples. Winter began when the river froze, summer when the ice went out and the salmon arrived. Commerce, customs, legends, gods, wars, plagues, and news all moved along it. The watersheds of the Yukon and other rivers south of the Brooks Range and interior Alaska generally remain occupied by Athapascan Indians today, but the questions of origins and identity are only partly answered by legend and the remains of old settlements and campsites. Very little is known of the lifeways and technology of these early peoples who spread from the western sub-Arctic down the Pacific coast to northern Mexico. We do know that the ancestral Indians followed the spawning salmon into the Interior, lived with the seasonal migration patterns of the caribou herds, and learned the habits of the moose, bear, furbearing animals, and waterfowl.

Despite some significant discoveries, the ancient Athapascans essentially remain strangers to modern scholars. The major archaeological site in the Yukon Region, the Campus Site, was discovered in the 1930s on a hill overlooking the Chena River near the university at Fairbanks. Other significant sites are located on the lower Koyukuk drainage, south of Huslia, at Donnelly Dome, Tangle Lakes, Teklanika River in the eastern part of Mt. McKinley Park, and at Healy Lake (Figure 186). The Healy Lake site has been radiocarbon dated to 11,000 years Before Present (BP) and is the oldest known site in Alaska. Several others have been located along the lower and central Yukon River, the trans-Alaska pipeline corridor, the lower Tanana, Kantishna, and Tolovana Rivers, and at Lake Minchumina.

Historical and comparative linguists classify the ancient settlers in the region and their descendants as Athapascan Indians, primarily on the basis of similarities in language (Figure 187). The word "Athapascan," with all its varieties of spelling is not itself an Athapascan word but is rather an Algonkian word used by the Cree Indians to indicate the "strangers" who lived to the north.

While it is generally true that interior Alaska is the homeland of the Athapascan Indian, in several areas Eskimos and Indians live in close juxtaposition and in others the intermixture of these two cultures has been so great that distinctions are difficult to make.

To describe the territorial groupings of Native peoples, the Yukon Region is divided into the Yukon delta, Koyukuk-lower Yukon, upper Yukon-Porcupine, and Tanana areas. Yupik Eskimos predominate in the delta.

On the Yukon delta the settlement patterns were coastal and riverine. Settlements were located and grew in size in direct relationship to the availability of food and shelter. Villages and individuals established rights to specific territory, land use, and water which were generally respected and guarded against foreign encroachment.

Almost all villages were occupied in winter and periodically in summer. Permanent villages were distinguished from fishing, sealing, or berrying camps by the presence of one or more community houses—kazgis—that were often large enough to accommodate visitors from neighboring villages.

Each large village had a chief who was advised by a council of elders. Leadership was based on an organization rather than simple command:

The chieftainship was an office supposedly filled by the most capable man in the village, and though ideally it was hereditary, any man with the required qualifications could be groomed for its duties. Basic requirements were intelligence, wisdom, unselfishness, fairness, bravery, wealth, (or the ability to acquire it), but above all, diplomacy and ability to arbitrate and get along with other tribes (Ray 1967).

As in all early Alaskan Eskimo societies, Northwest Region Eskimos depended on the biotic resources of the environment for survival. This dependence is still evident. Hunting of caribou, whales, walrus, and small sea mammals led to the development of separate but interrelated subsistence patterns among northwest Eskimo groups.

Koyukuk Athapascans live along the Koyukuk and middle Yukon. Their original territory covered parts of the lower Yukon drainage as well as the drainages of the lnnoko and Koyukuk Rivers. The Ingalik Athapascans occupied the areas around Anvik-Shageluk, Bonasila, and Holy Cross-Georgetown (Figure 186).

[insert oversize fig 186]

Villages were usually located on or very near major rivers—the lnnoko, Yukon, and the Koyukuk. These villages functioned as base occupation centers complimented by the many seasonal, family, and group fish camps along the rivers and interior hunting and trapping camps. The distinctively Athapascan occupancy of this region was somewhat modified by the presence of Yupik Eskimo settlements above Holy Cross, near the Yukon-Koyukuk confluence, and by the presence of the Inupiat Eskimo along the upper reaches of the Koyukuk. There was a strong sense of territory among all groups. Historically, some instances of territorial conflict occurred between Athapascan and Eskimo, but both groups generally lived in peaceful and productive proximity.

Within historic times there appear to have been five principal groups of Kutchin Athapascans in the upper Yukon-Porcupine regions—the Kutchakutchin of the Yukon Flats area, the Hankutchin of the upper Yukon, the Natsikutchin in the Chandalar drainage, the Ventakutchin of the Crow River area, and the Tranjikutchin of the Black River. Other Kutchin subgroups, such as the Tennuthkutchin of Birch Creek and the Tatsakutchin of Rampart, were decimated by disease and have disappeared.

Today the Kutchin in Alaska are represented by three groups: the Kutchakutchin, the Hankutchin, and the Natsikutchin. The Kutchakutchin traditionally occupied both banks of the Yukon and Porcupine, but their principal settlements were concentrated in the Yukon Flats area. While there has been considerable mixing throughout the region, Stevens Village, Beaver, Birch Creek, Circle, and Fort Yukon are identified as Kutchakutchin. The Hankutchin occupied the area between the Alaska-Canada border and the upper areas of the Yukon Flats near Circle. While historic evidence of several Hankutchin villages does exist today, only Eagle Village can still be characterized as primarily Hankutchin. The original village, called John's Village, was located a few miles downstream from the present site of Eagle and Eagle Village. The development of a white community at Eagle served in part to attract the Hankutchin to the Eagle Village location a few miles upstream from Eagle. The Natsikutchin were nomadic people quite similar in livelihood patterns to the Nunamiut or inland Eskimos. The Natsikutchin often hunted the caribou north of the Brooks Range and occupied the country from the Porcupine River north to the Romanzof Mountains in the Brooks Range. Arctic Village and Venetie are Natsikutchin villages.

|

Figure 188. Estimated Distribution of Alaska Native Population |

|||||||||||

|

Circa 1740-80 |

Circa 1839-44 |

1880 |

1890 |

1910 |

1920 |

1929 |

1939 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

|

|

Northwest Coast Indian |

11,800 |

8,300 |

8,510 |

5,463 |

5,685 |

5,261 |

5,895 |

6,179 |

7,300 |

7,900 |

8,300 |

|

Tlingit |

10,000 |

6,565 |

7,712 |

4,115 |

4,426 |

3,895 |

4,462 |

4,643 |

5,500 |

6,000 |

6,300 |

|

Haida |

1,800 |

1,735 |

798 |

395 |

530 |

524 |

588 |

655 |

750 |

800 |

800 |

|

Tsimshian |

953 |

729 |

842 |

845 |

881 |

1,050 |

1,100 |

1,200 |

|||

|

Northern Athapascan Indiana |

6,900 |

4,000 |

4,057 |

3,520 |

3,916 |

4,657 |

4,935 |

4,671 |

5,100 |

6,500 |

8,300 |

|

Interior (Ingalik, Koyukan, Tanana, Kutchin) |

4,800 |

2,100 |

3,193 |

2,531 |

2,922 |

3,657 |

3,935 |

3,671 |

3,900 |

5,000 |

6,400 |

|

Pacific (Eyak, Athena, Tanaina) |

2,100 |

1,900 |

864 |

989 |

994 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,200 |

1,500 |

1,900 |

|

Western Eskimo |

26,600 |

24,500 |

17,617 |

13,871 |

15,279 |

14,990 |

17,171 |

19,169 |

19,320 |

24,800 |

31,400 |

|

Inupik (Arctic) |

6,350 |

6,000 |

3,492 |

2,336 |

3,305 |

3,487 |

4,227 |

5,489 |

5,600 |

6,200 |

8,060 |

|

Yupik |

|||||||||||

|

Siberian (St. Lawrence) |

600 |

600 |

500 |

267 |

292 |

300 |

389 |

505 |

540 |

636 |

785 |

|

Cux (Nunivak) |

400 |

400 |

408 |

373 |

301 |

184 |

181 |

215 |

203 |

232 |

258 |

|

Yuk (Bering Sea) |

10,550 |

10,000 |

9,702 |

8,734 |

8,502 |

8,313 |

10,184 |

10,414 |

10,617 |

15,232 |

18,397 |

|

Suk (Pacific)b |

8,700 |

7,500 |

2,242 |

2,161 |

2,897 |

2,706 |

2,190 |

2,546 |

2,360 |

2,500 |

3,900 |

|

Aleutc |

12,000 |

2,200 |

2,628 |

1,679 |

1,451 |

1,650 |

1,857 |

2,006 |

2,180 |

2,800 |

3,100 |

|

Unclassified |

184 |

821 |

125 |

433 |

|||||||

|

TOTAL ALASKA NATIVE |

57,300 |

39,000 |

32,996 |

25,354 |

25,331 |

26,558 |

29,983 |

32,458 |

33,900 |

42,000 |

51,100 |

|

a Division by Interior and Pacific Athapaskin estimated for 1920, 1929, and 1939. |

|||||||||||

|

b Identified as "Aleut" in recent census and other reports. Belong to Koniag (Kodiak Island) and Chugach (Prince William Sound). Classified by Oswalt as Pacific (Suk) dialect of Yupik. |

|||||||||||

|

c 1920-1950 classified by location. 1960-1970 includes estimates of urban and relocated Aleuts. |

|||||||||||

|

Source: G.W. Rogers, 1971. Alaska Native Population Trends and Vital Statistics, 1950-1985. |

|||||||||||

Very little is known of the Tanana and Nabesna Athapascans who occupied the Tanana region. They appear to have been small in number, and very few settlements have been identified. .The principal Tanana settlements were probably along the Tanana River drainage above the confluence of the Yukon with the Tanana as well as immediately below it. One settlement of the Tanana has been identified at Lake Minchumina and another close to the modern settlement of Tanana. The Nabesna Athapascan record is even sketchier, although it is known that they occupied the drainages of the upper Tanana tributaries and the Nabesna and Chisana River drainages.

Athapascan Indians in Alaska generally lived in small groups in which the primary unit was the family, composed of a man, one or more wives, their children, and perhaps one or two old people. Sometimes two or more such families occupied the same dwelling. Several such households lived near each other and worked together, forming the local group. The next order of social organization was the band, formed by several local groups. The core of Athapascan social life, however, was the family and household. Local groups and bands met for special occasions, to arrange marriages, and to renew ties with family and friends.

Leadership and social control were loose and usually vested in family and local groups where criticism, reward, and punishment were most effective. There were no "tribal chiefs," although prominent local leaders were called chiefs. Leadership shifted according to specific need. During times of illness or other crises the ablest shaman assumed leadership, while hunting parties were led by the best hunter. Occasionally, a group of elders would gather to deliberate and make decisions, but generally all adults were free to run their own affairs.

|

| Mrs. Martha George and Mrs. Margaret Mayo. Mrs. George lived in Rampart around the turn of the last century. Her parka has fish skin trim. |

In early spring small family and household groups packed their gear and moved to spring camps of skin tents and brush huts. Each family, group, or band exploited a well-defined territory, which usually included proprietary fishing sites, beaver, muskrat, and waterfowl hunting areas, and berrying grounds. The hunting of waterfowl and muskrats was the first activity. As spring progressed birch bark was collected for use in canoes, baskets, roofs, and walls of winter houses and fish drying sheds. Birch particularly was used in making snowshoes, sleds, and toboggans. Birch fungus was used in indoor fires, red or diamond willow and other woods for making bows and arrows, and conifers for firewood and dwellings. Plants supplied herbs to treat influenza and to make poultices for injuries and natural dyes for decoration. Plant lore among the Athapascans was highly developed.

After muskrat hunting the people moved to fish camps to repair last year's fish traps, set up tents, and build brush and moss shelters. This was the time of a major catch of whitefish. Traps were generally made of thin strips of spruce tied with spruce roots. Frequently, the traps were used in conjunction with wings or weirs in small streams to channel the fish into two-part conical basket traps or nets. The catch was dried, bundled, and moved to the next camp or stored in caches for the lean months.

Later in the season the men began framing new birchbark canoes. The women sewed on the bark covers with spruce root, and all seams were waterproofed with hot spruce pitch. When most of the work on canoes was completed, the women began the yearly production of baskets and other utensils.

In June the people moved to summer camps on large rivers and lakes. Usually, several households or local groups would meet at appointed locations to celebrate the spring hunting, trade, and feast.

Summer shelters varied from the caribou hide tent popular among the Koyukon and the Kutchin to the brush and moss-covered shelter favored by the Ingalik and other Alaskan Athapascan. Other groups, particularly those on tributaries of the Yukon, sided their fish-drying sheds with willow, roofed it with bark, and used one end of it as living quarters.

Very early in June the shelters were ready, and the second major task of the season began. Fish storage caches and drying sheds were renovated, drying racks were set up along the riverbanks, and the women repaired and made willow bast gill nets. Large traps were set in special places along the main river and its tributaries. By mid-June they were ready for the first salmon runs.

Salmon were the basis of their subsistence. Smoked and dried fish were the winter staple food. Oil provided light, and in some parts of the Yukon, the skin was used to make waterproof parkas and boots. To the Natives it was a joining of man's spirit with the salmon that guided a plentiful and successful fishing season. All the villagers moved upstream following the salmon spirit and placed traps and nets in the most productive areas.

As summer settled into an orderly routine more men took to hunting, and except for a "trap boss," the maintenance of the camps was left to the women. While the men were away the women spent much of their spare time preparing clothing for winter and summer use. They also worked on quivers, game bags, dog packs, tumplines, baby carriers, and ropes made of moose or caribou hide. Toward the end of summer several varieties of berries were picked, especially blueberries, cranberries, crowberries, rose hips, gooseberries, service berries, and currants and stored for winter use along with wild onions, rhubarb, licorice, and the leaves and sap of willow and birch. Snowshoes were repaired or new ones made, sleds and toboggans were renovated, and bows and arrows prepared for autumn caribou hunting.

Caribou were hunted by the Athapascans in much the same manner as they were by the Nanamiut Eskimo of the Brooks Range. Generally, the animals were driven towards specially prepared corrals or fences, which often ran for five or more miles, where they were caught in snares or killed with knives, spears, or arrows. Other hunters used snowshoes to run down the animals and shoot them with bows and arrows. During late autumn, as the caribou migrated southward, families moved to the fences or other good hunting areas to obtain meat and hides.

From late autumn through early winter the men continued to hunt moose and caribou. Bears in hibernation were killed in their dens, and smaller mammals and ptarmigan were taken in deadfalls and snares. Fish were taken through the ice with spears, lures, bone hooks, and traps and nets until the ice grew too thick.

Dwellings used from late fall through winter included logpole lodges and skin tents, the domed tents, Yukon lean-tos, and in northwestern areas subterranean houses with central hearths and tunnel entrances similar to those of the Eskimo. It was only after European contact that the log cabin became generally used among the Athapascans.

If the harvest had generally been good, people visited other regions to trade and feast, and during the winter solstice they gathered for midwinter ceremonies.

The period of western discovery of Alaska began with the Russian expedition of 1728, although there is evidence that the Russians first sailed through Bering Strait and explored northwestern Alaska as early as 1640 (Figure 189). Vitus J. Bering, a Dane in Russian service, was commissioned to undertake a voyage to determine whether Asia and the "Great Land" east of Kamchatka were separate continents. He sailed from the Kamchatka River in July 1728, discovered St. Lawrence Island and the Diomedes, and coursed through the strait that now bears his name into the Arctic Ocean as far north as 67 degrees north latitude. In 1729 he explored and charted the coast and established that Asia and America were separate continents, although fog prevented him from actually seeing the American mainland (Chevigny 1965).

|

Figure 189. Exploration Chronology in Northwest-Central Alaska, 1640-1924 |

|||||

|

1640 |

First European ship passed through the strait separating Asia and North America |

1831-1833 |

Mikhail Tebenkov (IRN) surveyed the Norton Sound area established Redoubt St. Michael in 1833, and was responsible for surveys of coastal waters and improvement of Alaskan charts |

1879 |

Northwest Passage navigated by Adolf Nordenskjold in Vega |

|

1725-1741 |

Expeditions of Vitus Bering |

1842-1845 |

Lavrenti Zagoskin (IRN) explored portions of Norton Sound and the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers |

1884 |

George Stoney and John Cantwell explore Kobuk River in separate expeditions; Cantwell explored Selawik Lake |

|

1778 |

James Cook explored the Bering Sea to Icy Cape |

1845 |

Americans began whaling in Bering Sea |

1885 |

Cantwell and Stoney separately explored Kobuk again; S.B, McLenengan explored the Noatak; Henry I. Allen explored Norton Sound |

|

1791 |

Joseph Billings of the Imperial Russian Navy (IRN) visited St. Lawrence Island |

1844-1854 |

Russian Hydrographic Department published charts of the Pacific Ocean, northwest North America, and the Bering Sea |

1898 |

Gold discovered at Cape Nome |

|

1803-1806 |

Adam von Krusenstern (IRN) explored the Siberian coast and later published an atlas of the Pacific |

1847 |

Search for lost Franklin Expedition began |

1898-1900 |

John F. Pratt supervised surveys of Bering Sea, Norton Sound, St. Michael harbor, and Port Clarence |

|

1816-1817 |

Otto von Kotzebue (IRN) landed on St. Lawrence Island, explored and mapped coastal areas of northwest Alaska |

1854-1855 |

U.S. Navy North Pacific Exploring Expedition |

1899 |

Harriman Expedition provided first full-fledged scientific report on Alaska |

|

1820 |

Glieb Shishmaref and Mikhail Vasiliev explored the coast from Kotzebue Sound to Icy Cape and later from Norton Sound to Cape Newenham |

1865 |

Shenandoah captured 10 American whaling vessels in Bering Strait in last hostile action of the American Civil War |

1900 |

Alfred Brooks of U.S. Geological Survey conducted extensive field work in Cape Nome and Norton Bay areas |

|

1826-1827 |

Frederick W. Beechey surveyed Bering Strait, coast above Kotzebue Sound, and Seward Peninsula |

1865-1867 |

Western Union Telegraph Expedition |

1906 |

Roald Amundsen completed first voyage through Northwest Passage in Gjoa |

|

1827 |

Feodor Lutke (IRN) cruised the Bering Sea below Norton Sound |

1877-1879 |

Edward Nelson studied history and ethnology of northwest Alaska |

1913 |

Vilhjalmar Stefansson's Canadian Arctic Expedition left Nome |

|

1921-1924 |

Knud Rasmussen's dogsled journey across the Arctic from Greenland ended in Nome |

||||

His reports of this voyage were never fully believed in St. Petersburg, but he was again commissioned to sail east. Bering's second expedition sailed in 1741, this time on a more southerly course to the mainland where he sighted Mount St. Elias from the Gulf of Alaska on July 16, 1741. The day before, Alexei Chirikov, commanding Bering's second ship the St Paul, made a landfall on Kayak Island. This sighting of Mount St. Elias is generally credited as the discovery of Alaska, although in reality Bering's 1728 voyage was equally productive. Bering died in the Commander Islands off Kamchatka, but the remnants of his crew along with Chirikov and the St Paul brought back quantities of blue fox, fur seal, and sea otter skins.

Their success inaugurated a period of ruthless and extensively profitable fur hunting in the Aleutians. During this early phase of the Russian occupation, the Yukon Region and interior Alaska generally remained relatively untouched since the fur trading activities of the promyshlenniki were concentrated in the Aleutians and moved eastward toward the Alaska Peninsula rather than north to the Yukon delta and Bering Strait (Figure 190). Until the late 1770s the Russians were fairly successful in protecting their enterprise in Alaska from others, but word of the Russian exploits encouraged other Europeans, particularly the Spanish, to move against what they considered Russian encroachment into their New World empire.

The English and French were traditional rivals of Spain and they soon began to explore Russian America. Moreover, the English and French had been engaged for years in a search for a Northwest Passage to the rich East India trade. In quest of the Northwest Passage, Captain James Cook in command of the English ships Discovery and Resolution, passed through Bering Strait in July 1778. Carefully exploring and charting the coast, Cook and his men sailed as far north as 70o45' north latitude. The expedition then retreated south to winter in Hawaii where Cook was killed by islanders in 1779. Following Cook's death Captain Charles Clerke took command of the expedition and returned to the Arctic. The Cook-Clerke voyage is an important landmark in the exploration of Alaska, for charts produced by the voyages provided the incentive for further explorations of the area.

Meanwhile, the Russian fur quest in the Aleutians and southeastern Alaska was consolidated into an increasingly well-regulated enterprise under the Russian American Company. Considerable credit is due Alexander Baranof, who was appointed manager of the Golikov-Shelikov concern in 1790, for making the Russian American Company into a powerful colonial monopoly and the de facto government of Russian America in Alaska.

In 1799 the company received a 20-year, renewable government charter, the right to employ Russian military personnel to conduct foreign trade, and to buy arms from the government, and in fact to be the vice-regal representative of the Russian government in Alaska. However, as far as the Yukon Region was concerned, the Russian American Company's activities were not yet significant. The charter recognized that the company's sphere of influence extended only as far as 58 degrees north latitude, and specifically recommended the establishment of new settlements and claims south of there (Figure 190). Nonetheless, from 1787 until Baranov's retirement as governor of the colony in 1817, several important explorations were made in the coastal areas of the territory which led Europeans and Americans further into the Athapascan territory.

In 1818 a party of explorer-traders crossed the Alaska Peninsula to the Bering Sea coast where they established the first post north of 58 degrees at the mouth of the Nushagak River in Bristol Bay. In 1829 a party from this post ascended the Nushagak and portaged across its source to discover the Kuskokwim River. The party then floated the Kuskokwim to the Bering Sea, and without knowing, came within 35 miles of the Yukon River.

In 1831 a naval officer, Lieutenant Michael Tebenkov, reconnoitered the Bering coast and was told by Natives of a mighty river which reached the sea just north of the Kuskokwim. Tebenkov did not reach the Yukon on this expedition, but he returned to the area in 1833 and found the "mighty river" of which the Eskimos spoke. Tebenkov reached the Yukon delta and built a fortified trading post, Redoubt St. Michael, on a barren, windswept island offshore.

There were never more than a thousand Russians in Alaska during the more than 120 years of their occupation, and Russian dominion over their Native "subjects" was tenuous where it existed at all. The Russian American Company relied to a great extent on Creoles, the children of Russian-Native unions. Andrei Glazunov, the "discoverer" of the Yukon, was a Creole who came with Lieutenant Tebenkov to establish St. Michael in 1833. During that winter he was commissioned to search out and chart the course of the Yukon and then to find and chart his way to the head of Cook Inlet where Anchorage now stands.

|

| The Russian Orthodox church at Russian Mission, circa 1900, the first such mission in interior Alaska, was established in 1851. After the Russians sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, Catholic missionaries became quite active in this area of the Yukon Region. |

In 1838 Malakov traveled northeast over the Bering Sea ice to Unalakleet and from there followed a portage to the Yukon River and traveled downriver some 50 miles to the mouth of the Nulato River where he found a small Indian village. He discovered that the village was a traditional trading place for the area's inhabitants. Coastal Eskimos came to the village with seal and whale oil, tobacco, and copper spears bearing the imprint of a forge in Irkutsk, which they in turn had received in barter from Chukchi Natives. Nulato was also known as a good fishing site. Malakov was well received by the local inhabitants and returned to St. Michael with 350 beaver pelts.

In late 1838 Malakov returned upriver to establish a trading post, only to find Nulato decimated by smallpox. Nonetheless, Malakov began construction of the post, and after much difficulty was trading effectively with the regional Indians by 1842.

The Hudson's Bay Company men, who had only heard of the Yukon before the 1840s, also were interested in exploring the Yukon Region and establishing trading posts of their own. Within a year of each other, two traders of the Hudson's Bay Company reached the Yukon. In 1844, James Bell starting west from the mouth of the Peel River, traveled the Rat River, portaged to the Porcupine River, and floated the latter to the Yukon. The year after, Robert Campbell reached the Yukon, 500 miles upriver from the Porcupine. Here the two rivers join to form what Campbell thought the beginning of the Yukon.

In late summer of 1846 Alexander Hunter Murray arrived at Bell's Peel River post. During the winter of 1846 Murray and Bell planned the establishment of a Hudson's Bay post on the Yukon River, and in the spring of 1847, Murray set out from Peel River for the Yukon. Some 300 miles upstream from the Indian trading site at Nuklukayet, on the great bend the Yukon makes as it crosses the Arctic Circle, Murray established Fort Yukon. This was the westernmost post of the Hudson's Bay Company and the first English-speaking enterprise in Alaska. In 1852 the Chilkoot Indians destroyed the second Hudson's Bay post at Fort Selkirk in Canada, and the upper Yukon was largely left to the Indians until the Americans arrived.

In 1857 Cyrus Field's ambitious plans to lay a trans-Atlantic telegraph cable were in serious difficulties. Perry Collins, another businessman, proposed an alternative overland telegraph line to run from Washington state through Canada, across Russian America, Bering Strait, and Russia and link up with the European telegraph system at St. Petersburg. Collins' scheme won official government support, and the Western Union Telegraph Expedition was organized to explore the proposed route, which included the Yukon valley.

In 1865 Robert Kennicott, a young naturalist, was sent to St. Michael to begin a survey of the route. Kennicott died under mysterious circumstances very early in the project, but not before he had sent two of his assistants, Mike Laberge and Frank Ketchum, on a reconnaissance of the river between Nulato and Fort Yukon. In November 1866 William Healey Dall was appointed to lead the expedition, With Dall was Frederick Whymper, an English artist commissioned to keep a pictorial record of the expedition. Dall, Whymper, Laberge, and Ketchum successfully completed the first basic reconnaissance of the entire course of the Yukon River in June 1867. When they arrived back at Nulato, a message awaited them:

Company has suspended operations. Reason: The Atlantic cable is a Success. We are all ordered home. United States bought Russian America from Russian government.

Since the 1850s Russian profits from the American colony had been dwindling, and alarmed investors attempted several new enterprises to improve the economic base. These included entry into the tea trade, coal mining operations at Port Clarence, and a contract to market Alaskan ice in California. None of these ventures could rival the profits gleaned from the fur trade, and expenses were enormous.

However, Alaska's importance never solely depended on its resources. Stretched over a vast area of the North Pacific, its location gave the region strategic values recognized by both Russia and America. In 1824 Secretary of State John Quincy Adams pressed for and won Russian permission for Americans to ply the waters of the North Pacific in the interests of legitimate business. In 1852 Senators William H. Seward and William Gwin sponsored legislation to map the area to facilitate whaling and commerce. Finally, in 1866 when William Seward was in his last years as Secretary of State, negotiations with Russian Envoy Edouard de Stoeckl resulted in the purchase of Alaska for $7.2 million.

Among those present at the final ownership transfer on October 13, 1867, was Hayward M. Hutchinson, who along with sea captain William Kohl, negotiated the purchase of the plant and entire inventories of the Russian American Company, including Redoubt St. Michael. St. Michael became the principal depot for goods destined for interior Alaska and northwestern Canada. Ocean-going ships transferred their cargoes to shallow-draft vessels at St. Michael for shipment upriver. As Yukon traffic boomed, so did St. Michael.

Hutchinson, Kohl and Company was not without competitors since several traders on the Yukon had organized the Pioneer Company, which established the first American trading post on the Yukon at Nuklukayet. The little company did not last long. Hutchinson, Kohl and Company, which had become the Alaska Commercial Company in September of 1868, decided to push its way into the Interior, and on July 4, 1869, the company's new 50-foot stern-wheeler started upriver to Fort Yukon, the first such voyage by a mechanized boat.

Captain Charles P. Raymond of the U.S. Army was sent along to verify the exact location of Fort Yukon, which the U.S. government suspected and the Alaska Commercial Company hoped, was in American territory. It was, and the British were politely ordered to remove themselves. The Alaska Commercial Company had been foresighted enough to send along their own traders, and they took over the Hudson's Bay establishment at Fort Yukon.

The Federal Government made very few provisions for governing Alaska. The customs, commerce, and navigation laws of the United States were extended to include the new possession, and criminal cases were tried in California, Oregon, and Washington. From 1867 to 1884 Alaska was governed by officials of the Army, Treasury, and Navy Departments.

From 1870 through the 1890s, Alaska's economic potential was more fully exploited. Americans enriched themselves with sea otters, salmon, and whales, and in 1879 the first gold mining operations in Alaska were established at the head of Silver Bay near Sitka. These basic industries, a developing tourist interest, and missionary activity in the area broadened public interest in Alaska.

Exploration of the newly acquired possession increased. In 1874 Lucien McShan Turner was dispatched by the U.S. Army Signal Corps to St. Michael, where he conducted meteorological observations and collected plant and animal specimens. In 1877 E.W. Nelson made extensive sledge journeys throughout the area, including one of 1,200 miles through the Yukon delta. His studies and observations of the inhabitants of the area remain today an enduring contribution to knowledge of the region.

In 1883 the U.S. Army initiated its long-planned exploration of interior Alaska, led by Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka.

. . . Schwatka and his party drifted through a region that had changed little over the centuries. The aboriginal pattern of life had of course been somewhat disrupted by the appearance of Russian traders and priests in the early years of the nineteenth century on the lower Yukon River and by their British counterparts from the Mackenzie River (the Reverend Robert McDonald had founded an Anglican mission at Fort Yukon in 1862), but life for the natives had not been altered essentially. The Indians greeted Schwatka's raft with salutes from firearms and asked for tobacco and tea but otherwise behaved in their traditional manner. Bows and arrows were more common than firearms; brush huts and skin tents were their habitations. Their livelihood depended in large part upon the summer run of Pacific salmon, the unfailing resource that dictated the natives' seasonal movements, and they dressed and sheltered themselves as their ancestors had done. (Hunt 1974)

In 1885 Lieutenant Henry T. Allen led another notable exploration of Alaska. Allen started from the Copper River delta with F.W. Fickett and Cady Robertson of the U.S. Army and two prospectors, Peder Johnson and John Bremmer. The party explored the Copper River, went up the Chitiana valley, where they noted large copper deposits, and went on to the head of the Chitistone. Allen then traveled up the Slana and down the Tetlin and Tanana to the Yukon. Allen and Fickett crossed to the Kanuti, to the Koyukuk, and portaged to the Unalakleet and down to St. Michael. Allen's expedition was the first successful attempt to cross from the Prince William Sound directly to the Yukon basin.

The published accounts of these and other expeditions increased public interest in the area, and their occasional remarks about the presence of gold began to attract prospectors to the region.

. . . prospectors followed stream after stream, panning the sand of their innumerable sandbars. If, after washing the sand away, enough glittering flakes of gold dust remained, that stretch of the river was worked more thoroughly. The prospectors shoveled the sand into a crude rocker, which caught the heavy gold as the sand passed through. With luck and hard work a man could pan enough gold by this method to keep himself in provisions. Once winter had set in and the ground was frozen and snow-covered, little work could be done. Some intrepid men continued to prospect, even after the freeze-up, until the snow grew too deep for travel, but most settled quickly into what comfort they could supply in their winter shelter, spending their time cutting wood for the stoves and hunting for game to supplement their food stores. (Hunt 1974)

These pioneer prospectors found only fur traders in the Yukon basin, but the traders quickly adjusted their operations to the potential business offered by the prospectors. Many of the early traders were also part-time prospectors. They traded for a living and prospected for the love of the search and the ever-present hope of striking it rich. After 1867 there was no reason to keep the area closed to newcomers, as had been the policy under the Hudson's Bay Company and the Russian American Company. As prospectors found their way into the Yukon basin, they were welcomed rather than resented, and very quickly the trading posts began to stock mining equipment and supplies for prospectors as well as the Natives. As a result, prospectors could stay longer in the Interior and prospect more intensively. Trading posts became stores for miners and grew into communities. The growing number of prospectors increased strikes and stampedes began.

The first major break in the pattern of Yukon prospecting came in the fall of 1886, when Howard Franklin made his strike of a rich placer field on a tributary of the Forty Mile River. All the gold strikes before his had been found on sandbars along the Canadian stretch of the Yukon River. Just before Franklin's strike the mining picture had been brightened a bit by the relatively high yield of the Stewart River sandbars, where about seventy-five miners took some $75,000 in 1875-76. But the gold on Forty Mile River was not confined to sandbars—it was there all over the region in rich bedrock deposits that straddled the American-Canadian border. Paydirt was found on Chicken Creek, Miller Creek, Franklin Gulch, and other tributaries of Forty Mile River. A stampede, small by later standards, of the prospectors on the Stewart River and elsewhere—Henry Davis and his partners among them—led to the development of the first mining community on the Yukon River. The settlement sprang up on a site approximately 25 miles from the American border, 34 miles downriver from McQuesten, Mayo, and Harper's post at Fort Reliance, which had been the supply center of mining along the upper Yukon River since 1874. With the Forty Mile discovery the pace of events on the Yukon river was accelerated. (Hunt 1974)

There were four major routes to the Yukon—the arduous Edmonton route overland across Canada, the inside passage to Skagway and Dyea and then over the White and Chilkoot Passes to the Yukon River, the Valdez Trail, and the all-water route up the coast to St. Michael and the Yukon River. The history of this period really is the history of these routes, the towns that sprang up along them, and the places to which they led (Figures 186 and 192).

Established trails along which roadhouses were spaced to provide some comforts were much less hazardous than those used on stampedes to remote places. The most important overland route into the interior was the Valdez Trail. Originally surveyed and built by the government, the "all American" route was intended to reach Eagle, on the upper Yukon. After the discovery of the Tanana valley goldfields, the trail was directed to Fairbanks rather than to Eagle. This route was open summer and winter; it closed only in late spring when thawing streams and mud made passage virtually impossible. (Hunt 1974)

Most of these little towns died, but Fort Yukon, Chicken, Beaver, Rampart, Eagle, Circle, and Fairbanks survived. Activities associated with the last three of these reflect late nineteenth and twentieth century events within the Yukon Region.

A trading post was first established at Eagle in 1874; another was built in 1886. The Native village of John's Village moved upstream and became established as Eagle Village, separate from the white community of prospectors, military, and traders. In 1898 the citizens of Eagle laid out a townsite and applied for patent to the land from the federal government. The initial application was rejected; the second application was ignored; and the ground included in the plat was instead made part of the newly designated Fort Egbert military reservation. After some difficulties with Washington, Eagle was finally allowed to incorporate. By 1900 the small city was one of the most important towns on the Yukon.

Eagle was the port of entry from Canada and it serviced the rich mining districts around the upper Fortymile as well as those on the Nation, Charley, and Tatonduk Rivers. Fort Egbert made it the military headquarters for northern Alaska for awhile, and it was the closest Alaskan gold town to the ice-free port at Valdez and the logical terminus for a telegraph line from there. In 1903 the telegraph line was completed, and Eagle became the communications center for the entire Yukon. For these reasons, Eagle was selected as the seat of the Third Judicial District of Alaska and home of its first appointed judge, James Wickersham, who arrived in Eagle in July 1900.

Eagle has lost much of its former eminence—the seat of the judicial district moved to Fairbanks in 1904; Fort Egbert was closed in 1911; the telegraph line fell into disuse; and the decline in steamer traffic on the Yukon reduced the commercial importance of the town.

The history of Circle City, or Circle as it is more usually called, is more typical of frontier gold rush towns. In 1893 two Creoles, known only as Sorresco and Pitka, who had been grubstaked by Jack McQuesten, a successful trader in the region for more than 15 years, discovered gold in paying quantities on Birch Creek. The Birch Creek mines were easily worked because they were shallow. Miners flocked to the area, and McQuesten moved his trading post down from the Fortymile to a spot on the Yukon about eight miles away from one of the loops of Birch Creek.

During late 1893 McQuesten helped and encouraged miners to winter in the area of his store. The sensible ones followed his advice, and a little settlement grew up around McQuesten's post. During the winter it was decided to call it Circle City since it was thought to be within the Arctic Circle. In the next three years the community grew rapidly and was known in the Yukon as the "Paris of Alaska." In its heyday Circle City had a library, an opera house, stores, saloons, gambling halls, a hospital, and even a debating society. In 1898 a military post was established there under Captain Ray, who was able to convince the residents to form a fire brigade, but he was unable to win their support for drains, sewers, and some sort of a garbage disposal.

It was at Circle that the self-government of a community by common agreement reached a kind of apogee. Miners at Juneau, Forty Mile, and Circle all followed a precedent set in the early days of the California gold rush and established mining regulations. The rules had always been supported by the American courts. At the first meeting in a new camp the men agreed upon the boundaries of their district, the extent of individual claims, and the method of staking and of giving notice. Then they elected a recorder to note all the locations that had been claimed by prospectors. The acceptance of this procedure by the miners and later by the courts prevented widespread chaos and disorder.

In Alaska, as elsewhere, the miners' meeting served another necessary function—that of keeping civil order. For lack of any other recognized authority, the miners' meeting acted as judge and jury to punish those accused of transgressions. Opinions varied on the effectiveness and integrity of the collective body in this role. Some considered the miners' meeting to be the purest form of democracy; others regarded it as akin to mob rule. (Hunt 1974)

Circle was almost abandoned when news of the Klondike strike reached Alaska in 1897; but the community survived, and today, though diminished in grandeur and size, remains an outpost along the mighty Yukon at the end of the Steese Highway from Fairbanks.

Fairbanks, unimaginatively named as a political gesture on the part of Judge Wickersham for an Indiana Senator who became an anonymous vice-president, is the most enduring and prosperous of the old gold rush towns. The city is located about 300 miles up the Tanana River where the Chena Slough enters from the north. Traders McQuesten and Harper traveled through the Tanana River valley as early as 1876, but it was not until 1901 that E.T. Barnette, a convicted swindler, incorrigible rogue, and soon to be founder of Fairbanks, arrived in the area. He knew that a telegraph line had been completed from Valdez to Eagle and had heard that the Army planned to lay out a road over a much-used trail between the two points and on up into the Yukon and Tanana country. In anticipation of the increased traffic, Barnette and his wife decided to open a store at what is now Tanacross.

Barnette hired a steamboat to get to Tanacross, but it could not get past the Chena Slough, and Barnette had to disembark with his supplies at a point he had spotted on the Chena River. As luck would have it, Felix Pedro, who made the first big strike in the Tanana Valley in July 1902, encouraged Barnette to set up shop right where he was. This was the inauspicious beginning of Barnette's Cache, later renamed Fairbanks.

The stampede following Pedro's find was all that Barnette had hoped for, but the flow slackened as soon as it became known that the gold around Fairbanks lay under several hundred feet of frozen overburden that required more time, capital, and equipment to mine than in previously discovered sites. Consequently, Fairbanks did not experience the rapid population growth typical of the Yukon gold centers.

Fairbanks was different in other ways, too; it was essentially a supply center for other mining towns that developed around it—Cleary City, Fox, Livengood, Ester, Nenana, Chatanika, Pedro Camp, Golden City, and Chena among others. The city started and remained during much of its early history, a family town. Miners from all along the Yukon came to Fairbanks, took steady jobs, and settled down with their families. By 1906 Fairbanks was a lively, prosperous community with electric lights, a water system, telephones, churches, schools, hospitals, and daily newspapers. The Tanana Valley Railroad connected Fairbanks with a number of the outlying towns.

Fairbanks did not have to endure lawlessness as Skagway and Nome had, for it had Judge Wickersham, virtually one of the town's founders because of his early move of the Third District court there. Fairbanks benefited by the presence of the court from 1904, and its citizens had legal authority to establish a town government. Other towns founded later also gained from the better organized judicial system and the privilege of civil government.

From his appointment as federal district judge in 1900 until his death in Juneau 38 years later, James Wickersham was the leading political figure of the territory. He served as judge for seven years and in 1908, he was elected congressional delegate, an office he enlivened for 18 years. (Hunt 1974)

By 1910 the gold rush era was in decline, and by 1915 it was over (Figure 192). Dredges, mechanical excavators, and other hydraulic equipment brought new life to the gold fields, but the heyday of the individual miner was gone. Corporate miners bought vast tracts of previously worked ground and reworked them for deep placer deposits. The tailings and derelict dredges from these activities are common sites in the region, particularly around Fairbanks.

Throughout the gold rush days, Alaskans were clamoring for more self-government. The Organic Act of 1884 created some civil government for Alaska, and in that same year the first Alaskan governor, J.H. Kinkead, was appointed (Figure 193). In 1898 the Transportation and Homestead Acts were passed. The first freed railroads in Alaska from the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the second restricted homesteads to 80 acres and shoreline entries to 80 rods or less. Many Alaskans argued that 80 acres was insufficient to support a northern homesteader, and they moreover felt that it provided too much of the shoreline for the canneries then booming in southeast and southwest Alaska. In 1899 a Criminal Code for Alaska was enacted, and in 1900 the Carter Bill providing for a full-fledged civil code in the territory, was passed. That act also provided for the transfer of the territorial capital to Juneau from Sitka as well as for establishing more effective municipal governments. In 1906 an Alaska delegate bill provided for a nonvoting representative to Congress.

In 1912 Alaska was granted territorial status with a bicameral legislature which worked diligently to secure full rights for Alaskans. Among its first acts was to enfranchise women, seven years before the federal government. It also requested that Congress liberalize the land laws to encourage and promote settlement in Alaska, petitioned Congress to end land reservations and withdrawals and to rescind some already made, and requested better and more roads and lower freight rates. The second legislature provided for citizenship for Indians and Eskimos, a means to establish municipal governments, old-age pension plans, a district road system, and a uniform school system and board of education. Congress was successfully persuaded to build a federally-owned and -operated railroad between Seward and Fairbanks, and work began in 1915. In October 1921, the territorial legislature established a college on a site overlooking the Tanana and Chena valleys four miles south of Fairbanks.

The period of the First World War was generally disastrous for Alaska and the Yukon valley. Gold production declined drastically; many Yukon-Tanana Valley settlements were largely abandoned; and Fairbanks suffered as the war drew off a considerable portion of its younger men. The completion of the railroad to Fairbanks in 1923 helped to revive the area somewhat, but growth was modest until World War II when military bases and a strong infusion of federal money for construction of roads and airports revived the state and local economies.

Within recent years three events have changed Alaska and the Yukon—the granting of statehood in 1958, the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971, and the discovery of extensive oil fields in Alaska between 1950 and the present.

—As the final push of almost a half a century of dedicated, if somewhat sporadic effort, the statehood movement of the 1950s pulled together diverse and frequently conflicting interests and molded them into a common desire for increased self-government and local control over the territory's natural resources. A major product of this final effort—Alaska's constitutional convention—built upon the consensus and enthusiasm generated by the statehood cause, and in the process, rose to high levels of idealism and dedication. The result was a very successful and a widely supported state constitution. (Fischer 1975)

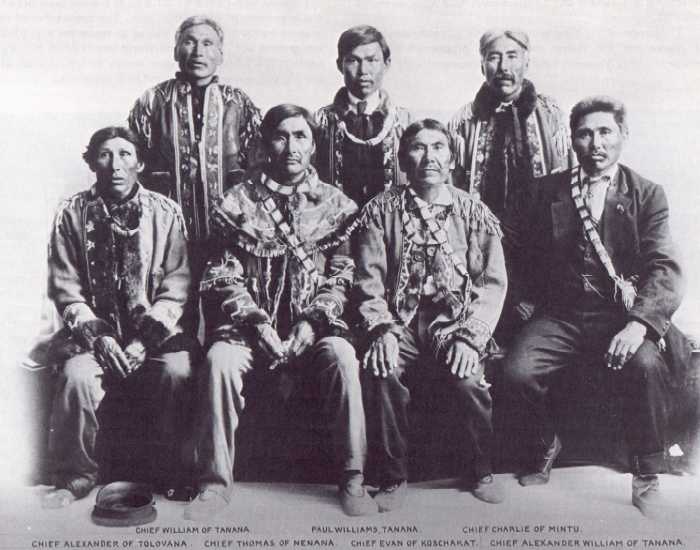

ANCSA established two Native regional corporations in the Yukon Region, Calista and Doyon, which will have an increasing influence on politics and economics in the state. The independence and leadership of the Tanana Indians was well-expressed in 1915 when the first meeting on Native land issues outside of the councils of the Tlingit and Haida in southeast Alaska, took place July 5-6, 1915, at the Thomas Memorial Library in Fairbanks.

Six Indian chiefs of the Tanana Valley, a number of village headmen, an interpreter, and a concerned Episcopal missionary met with a number of United States government officials including then-delegate to Congress James Wickersham, to talk about their need for land, education, and work as white settlers began adversely affecting their traditional subsistence way of life. It was at this conference that Natives in the area first stressed their desire to own the land they had always used.

Chief Thomas, of Nenana and Wood River: . . I am going to suggest one point, and that is that all of us Alaska natives and other Indians will agree with us, that we don't want to be put on a reservation. You people of the Government, Delegate Wickersham, Mr. Riggs, and Mr. Richie, you people don't go around enough to learn the way that the Indians are living, so we want to talk to you to explain our living to you, for we are anxious to show your people.

Chief Charley, of Minto: —I ask you not to let the white people come near us. Let us live our own lives in the customs we know. If we were on Government ground, we could not keep the white people away.

The Rev. Guy H. Madara, Episcopal minister in charge of all Episcopalian missions in the Tanana Valley, summed up his opinions this way:

—There is in the Indian life one very sweet feature, their mutual helpfulness. There is no such thing in an Indian village as one person having plenty and others being hungry. If one person has luck and gets a black fox and sells it, he has plenty of grub. He stores it in a tent or cabin and everybody goes in and eats. If one man kills a moose, this moose belongs to the whole village. That is what we call a community life. It would be too bad if that were taken away, which it certainly would be if they had to all live on separate allotments.

The reservation would result in the Indian soon perishing for they could not live in one place. Today the Indians are self-supporting and independent. They do not bother anybody to give them grub. They do not ask the Government for anything. (Patty 1971 )

|

| At a Tanana Chiefs conference

on July 5 and 6, 1915, Native leaders established some of the concepts used

by Congress to establish guidelines for the Alaska Native Claims Settlement

Act of 1971. At this conference Chief Evan of Cos Jacket (Koschakat) strongly

expressed the position of his people against reservations:

I remember ever since the ground was bought from Russia by the United States Government when we used the stone axe and the flint match, when I was a small boy. We have never had a chance to see the Government officials and tell them what we wanted. I have heard that the United States Government was supposed to be a good Government, and according to reports that I have heard, they even protect the dogs in the streets. And if the Government is able to protect the dogs in the streets, it should be able to look out for us. I am the son of old Ivan, and when he died long years ago, I took his place and have represented the people ever since. I am an old man now and sick, and likely to pass away at any time, so it makes no difference to me, but I am a friend of my people and I want to look out for their interests, and this will be the last time that I will consult with the Government officials . . . you must remember that I am making this statement in the name of the natives, all the natives that are in this district here. I am making this statement because I consider that all these natives that I represent I am sure do not want to be put on a reservation. They don't want to have one and therefore I am making this statement for the natives I am here to represent. (Patty 1971) |

The discovery of oil in the North Slope and the construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline have reinforced Fairbanks' role as a transportation and supply center to interior and arctic Alaska. The greatest impact of these activities is in the central Yukon and Tanana Subregions crossed by the pipeline. Although this boom, which has brought thousands of "outsiders" to the region, is considered temporary by many, only history will tell how permanent and profound these changes will be.

The population of the Yukon Region in 1970 was 60,984, or 20.2 percent of the total state population (Figure 194). The population density was one person to approximately 3.3 square miles. The white population was reported to be 78.3 percent, while the remainder was Alaska Natives (Figure 195).

The relatively small Fairbanks North Star Borough area contained 45,864 persons, or 75.2 percent of the region's total population. The remainder of the population was located in small villages scattered along major rivers.

Population growth has been most rapid in the Fairbanks area, which serves as a supply and transportation hub for oil- and gas-related activities along the trans-Alaska pipeline and haul road route as well as other mineral exploration throughout the northern half of the state.

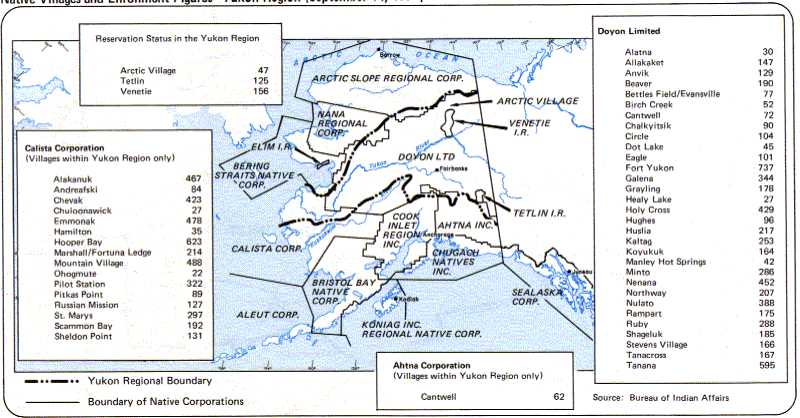

The census divisions included in the Yukon Region and the populations of the communities reported in the 1970 census are shown in Figure 196. Figure 197 shows a comparison of age-sex distribution between the state and the Yukon Region for the years 1960 and 1970. The relatively youthful population of both is clear. Villages claimed by the Native corporations under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and the number of Natives that have enrolled in the various villages are shown in Figure 198.

Figure 198. Native Villages and Enrollment Figures—Yukon Region (September 14, 1974)