Aquatic Animals, Marine

Plankton, Invertebrates, and Fish

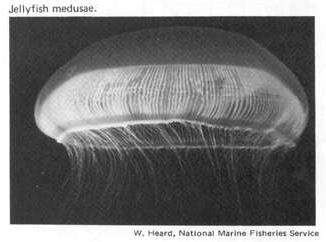

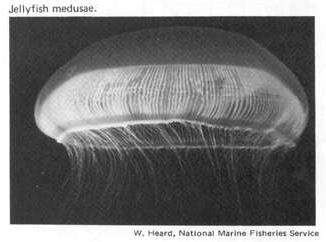

The oceanography of the eastern Bering Sea is dominated by northward-flowing currents. Because of this, plankton in Norton Sound and the southeastern Chukchi Sea is very similar to that of the Bering Sea. This area is characterized as having moderate standing crops of zooplankton. The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (1972) reported between 50 and 200 milligrams of zooplankton per cubic meter of surface water. General features indicate higher zooplankton volumes in offshore waters in association with major currents, while inshore waters, such as Kotzebue Sound, have lower plankton volumes. Extreme maximum volumes as high as 40 milliliters of zooplankton per cubic meter were measured by English (1966). Species that spend their entire lives as plankton (holoplankton) are abundant, while the larvae of benthic forms (meroplankton) are found sporadically.

Copepod crustaceans are the most abundant holoplankters. Characterizing the warmer, lower salinity nearshore waters are such species as Eurytemora Pacifica, Arcartia clausii, and Evadne nordmani. In the colder, higher salinity offshore waters Metridia lucens, Calanus plumchrus, and Eucalanus bungii predominate. South of Bering Strait Calanus tonsus is found in offshore waters, while in Norton Sound Tortanus discaudatus, Epilabidocera amphitrites, and Centropages mcmurrichi are common.

Arctic benthos tend to release well-developed larvae which spend a short portion of their lives as planktonic forms (Johnson 1953). Some of the more common meroplankters of this region are echinoid echinoderm larvae, polychaete annelid larvae, bivalve mollusc larvae, and barnacle larvae. Meroplankton seems to indicate the presence of benthic fauna.

The benthos of this region reflects the nature of the bottom substrate since many of these benthic organisms remain in one place throughout their entire lives. Benthic fauna distribution is also influenced by salinity, depth, water temperature, and dissolved oxygen concentration. Nearer shore, where rocks and large particle substrates predominate, the main benthic inhabitants are suspension feeders, scavengers, and predators. Further offshore, where substrates are primarily silts and sandy silts, deposit feeders dominate (Stoker 1973).

Echinoderms, tunicates, crustaceans, molluscs, and polychaete annelids are the most common benthic forms. Greatest diversity of species occurs in the molluscs and polychaete annelid groups. Small tanner crabs occasionally frequent this area. Small king crabs are found in Norton Sound. Several species of shrimp and the soft coral Eunephthya are also common. The dominant echinoderm is the brittlestar, Amphiodia craterodermata (Feder and Mueller 1974). Although molluscs and polychaete annelids are the most diverse groups, amphipod crustaceans and echinoderms are the most numerous. Polychaete annelids comprise approximately 50 percent of the total weight of benthic organisms in shallow Norton Sound (Stoker 1973).

Benthic or demersal fish distribution is determined primarily by temperature and salinity. For example, the yellowfin sole occupies shallow, warm waters, while the Bering flounder inhabits deep cold waters. The fourhorn sculpin inhabits the lower salinity coastal waters. Generally, fish in this region are sparsely distributed and smaller than in areas further south.

Predominant demersal fish in Norton Sound are members of the flatfish family. The large number of juvenile flatfish indicates that these species reproduce locally. Common types are rock and yellowfin sole, saffron cod, and several species of sculpins. Near St. Lawrence Island, Pacific cod are frequently encountered (Ellson et al. 1949). To the north, Arctic cod and Bering flounder become the predominant demersal species, and sculpins are also fairly common.

In Norton Sound, smelt and herring are the more common pelagic fishes. The large population of fall spawning herring in Golovin Bay is unique. To the north, herring and smelt remain common, while capelin and sand lance are also often encountered. These pelagic fishes in the northern portion of this region provide food for large coastal bird colonies.

Offshore migratory routes of salmon in this area are not well known. Yonemori (1967) found mature chum salmon moving eastward north of St. Lawrence Island and northeastward between St. Lawrence Island and the Yukon delta as they entered this region on their return spawning migration. Few immature salmon were found in these offshore waters.

|

|

|

Birds

Large numbers of oceanic birds inhabit the Bering Sea. They include the black-footed albatross that travels throughout the oceanic environment, nesting as far away as islands in the western Pacific Ocean and summering in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. The slender-billed shearwater, which nests as far away as southern Australia, is also found in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Other conspicuous oceanic species include the northern fulmar, fork-tailed storm-petrel, phalaropes, and jaegers.

The edge of the pack ice, as it advances southward in winter and retreats northward in spring, is a conspicuous feature of the Bering and Chukchi Seas and important habitat for marine birds. Murres, guillemots, puffins, auklets, jaegers, fulmars, and others feed in and beneath the ice edge and rest upon it, taking advantage of the moving food supply and shelter it affords.

Such colonial cliff-nesting birds as murres, puffins, and auklets, which breed along Alaska's coasts, also winter in the open ocean and take all their food from the neritic zone. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has mapped the significant colonies of cliff-nesting birds in the region and the largest of these are shown in Figures 136 and 138.

In the Kotzebue Sound Subregion, seabird colonies are found on Chamisso and nearby Puffin Islands, part of the existing Chamisso National Wildlife Refuge. Horned puffins, murres, kittiwakes, and gulls nest on Puffin Island and its associated islets and neighboring mainland cliffs.

Cape Lisburne supports the northernmost major bird colony on the west coast of North America. About a million birds, mainly common and thick-billed murres, black-legged kittiwakes, horned puffins, glaucous gulls, pelagic cormorants, tufted puffins, and black and pigeon guillemots, are raised there annually. Between Cape Lisburne and Point Hope, more than a dozen different colonies harbor smaller numbers of similar species.

Cape Thompson has at least five colonies containing 400,000 seabirds of essentially the same species as at Cape Lisburne. Peregrines, gyrfalcons, and rough-legged hawks also breed along sea cliffs near these capes (Williamson et al. 1966).

Birds nesting at Cape Thompson are believed to have taken 13,000 metric tons wet weight of food from the sea in a single breeding season (Swartz 1966). Other seabirds, including glaucous-winged, herring, mew gulls, pomarine, and parasitic and long-tailed jaegers, frequent the Cape Thompson area and some probably nest there.

St. Lawrence Island in the Norton Sound Subregion supports six major colonies of such species as auklets, murres, puffins, guillemots, gulls, and cormorants. Murie (1936) recorded 20 species of seabirds there. A colony on Little Diomede Island supports more than 100,000 birds of 22 species, 16 of which are known to nest there. Nearby Fairway Rock also supports a major colony that includes eight species estimated to number more than 100,000 breeding pairs.

King Island, Sledge Island, Egg, and Besboro Islands in Norton Sound and Cape Denbigh, Bluff, Rocky Point, and Cape Darby on the southern coast of the Seward Peninsula also support seabird colonies. The one at King Island may contain more than a million birds of at least seven species (Alaska Department of Fish and Game 1973).

| [insert Puffin picture here] |

Left: Horned purrins nest in the region. Below: Glaucous gulls are among the earliest spring arrivals in the nesting cliffs at Cape Thompson. |

Mammals

The Bering and Chukchi Seas abound with marine mammals. Walrus, four species of seal, 10 species of whale, and polar bears occur regularly, and several other species, including, northern fur seal which are rare in the region, have been reported. These animals all occupy the neritic zone, some almost exclusively. For several seal species, ice takes the place of land and provides hauling grounds for resting and bearing young. Only one subspecies of harbor seal predominantly inhabits ice-free water, usually hauling out on land. Other seals in the region are ice-loving, or "pagophilic." Fay (1974) categorized the polar bear, walrus, all seals other than the one subspecies of harbor seal, and beluga and bowhead whales as maintaining regular contact with sea ice. He rated the killer, gray, humpback, fin and minke whales and the harbor porpoise as having some contact with ice and the fur seal as having none.

Those in the first group usually stay at the edge of the drifting pack ice, an area of high basic productivity protected from heavy seas by the ice itself. Some of the ice-loving seals may not follow the ice edge south in autumn. They remain north throughout the winter, living in the pack ice or sometimes even under shorefast ice.

Bowhead whales, while they follow leads and can break ice as thick as nine inches (23 cm), can become entrapped in the pack if they venture too far into it. Beluga whales cannot break ice this thick and do not penetrate as far into the pack. Walrus also can become entrapped by solid ice and not be able to reach the water to feed (Fay, in press).

Burns and Morrow (1973) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (1973) briefly described the distribution of significant marine mammals in the region.

Polar bears reside on sea ice except for some pregnant females which may hibernate in dens as far inland as 25 miles. Polar bears are abundant in the Chukchi Sea, but few pass south through Bering Strait (Lentfer 1970). They are at the top of the food web in the region, subsisting mainly on bearded and ringed seals. Since the ban on aerial hunting of these bears and the increase of human settlement, they often go ashore in search of food at Wales, Shishmaref, Kivalina, and Point Hope (Figure 141).

Walrus inhabit the edge of the drifting pack ice. They migrate north from the southern Bering Sea with the drifting pack in spring, becoming most concentrated at Bering Strait, and summer far north at the edge of the polar pack (Figures 139 and 140). Their food is primarily benthic invertebrates.

Bearded seal distribution is similar to that of walrus except that a small population remains in the Arctic during winter. They are most abundant in the region during their spring and fall migrations. They feed primarily on benthic invertebrates and fish.

Ringed seals are the most numerous seals in the region when landfast ice is present, even bearing and nursing their young there for four to six weeks beginning in late March or early April. They spend the summer north of the region on the drifting pack. Their food is benthic invertebrates and fish.

Spotted seals, the ice-breeding form of this species, are the most common seal in the region during the open water season, frequenting bays and river mouths and hauling out on isolated beaches. They winter at the edge of seasonal ice in the Bering Sea and drift northward with it in spring, moving to the coast as the ice disintegrates. Their diet is small fish and invertebrates.

Beluga whales winter in the south Bering Sea, moving northward into the region at the edge of and within the retreating ice pack. Some follow the pack northward and eastward into Canada, while others calve in Eschscholtz Bay in the Northwest Region. They eat such fish as salmon and ciscos along with squid and other invertebrates.

Bowhead whales are confined to the edge of the ice pack, which some years allows them to winter as far north as Bering Strait. They usually migrate near St. Lawrence Island, Wales, and Point Hope to their final summer grounds north of Canada. They feed on krill—swarms of planktonic invertebrates usually consisting of Euphausiids or amphipods.

Gray whales of the eastern Pacific breed in Baja California and migrate northward along Alaskan coastlines to the Arctic, usually after the ice has retreated, although they may also be found at the edge of the pack. They are most abundant in the region at Bering Strait and Point Hope during their migrations. They feed on planktonic crustaceans.

Humpback whales occur regularly in the region but are not abundant since they prefer ice-free waters. Their migration takes them from waters off southern California, Mexico, and Hawaii to summer in the north Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. They feed on krill.

Walrus takes advantage of the northward drifting ice pack to ease their spring migrations.

[Alaska Regional Profiles, Northwest Region, pp. 160-163]