Regional Setting

The Southeast Region stretches nearly 600 miles (966 km) along a narrow strip of mainland averaging 120 miles (193 km) wide, east of longitude 141 degrees west from Dixon Entrance on the south along the Canada-Alaska border to Cape Fairweather on the north. It includes the Alexander Archipelago lying directly offshore to the west. Sixty percent of the total land area lies on the mainland and the rest consists of islands lying immediately offshore for a total surface area of approximately 42,000 square miles (108,780 km2). The region is part of a major drainage system which extends into Canada (Figure 2).

Cross Sound divides the area into two parts. To the north the coast is regular and bordered by a low, hummocky, irregular coastal plain less than 200 feet (61 m) high and covered in part by the Malaspina Glacier, which separates the Coast Mountains from the Gulf of Alaska. South of the sound, the mainland of southeastern Alaska is dissected by an intricate system of fjords forming a complex of mountainous islands with summits 2,500 to 3,500 feet (762 to 1,067 m) in elevation. These spectacular fjords are believed to be former drainage courses that were eroded and deepened by glaciers and ice currents. These seaways are deep, many over 400 feet (122 m), and have rocky bottoms. The mainland strip often peaks as high as 10,000 feet (3,048 m). Many of the interisland waterways and major fjords and streams occupy long linear depressions, the most prominent of which is the Chatham Strait, a deep trench four to 15 miles (6.4 to 24 km) wide and at least 200 miles (322 km) long.

The Alexander Archipelago, an extension of the coastal mountains to the north, is about 300 miles (483 km) long and has hundreds of islands—65 exceed four square miles (10 km2), and six are over 1,000 square miles (2,590 km2). These six are: Prince of Wales (2,770 square miles or 7,174 km2), Chicagof (2,062 square miles or 5,341 km2), Admiralty (1,709 square miles or 4,426 km2), Baranof (1,636 square miles or 4,237 km2), Revillagigedo (1,134 square miles or 2,937 km2), and Kupreanof (1,084 square miles or 2,808 km2). The islands are separated by a system of marine features such as sounds, straits, canals, narrows, and channels. There are nearly 10,000 miles of shoreline along the islands and mainland.

The Chatham Trough divides the coastal St. Elias Mountain Range from the irregularly incised Boundary Mountains along the U.S. and Canada border. The coastal range in southeast Alaska consists of the Fairweather Range, the Alsek Ranges, the Glacier Bay Section, the Chichagof Highland, and the Baranof Mountains. The Fairweather Range, the most rugged in southeastern Alaska, is the coastal extension of the St. Elias Mountains.

The major rivers of the region originate in Canada, apparently as antecedent streams that were able to maintain their courses as the coastal mountains were thrust upward. The principal rivers are the Alsek, Chilkat, Klehini, Taku, Whiting, Chichamin, Unuk, Bradfield, Speel, Stikine, and Taiya. The largest drainages are the Stikine River (19,700 square miles or 51,036 km2), Alsek River (9,500 square miles or 24,611 km2), Taku River (6,700 square miles or 17,358 km2), and the Chilkat (1,230 square miles or 3,187 km2). Many have glaciers at their headwaters. Freshwater lakes vary in size from a few acres to several thousand acres in size and in type from coastal marsh to high alpine cirque lakes. Only Harlequin exceeds 10 square miles. Water storage is principally in the glaciers and winter snowpack.

Although no permafrost exists at lower elevations, the region contains extensive glaciers. The Malaspina Glacier, one of the largest ice masses on the North American continent, lies at the northwestern extremity of the region. The mountains of the St. Elias Range rise to elevations of 14,000 to 19,000 feet (4,267 to 5,791 m) from a jagged mass of peaks having elevations of 8,000 to 10,000 feet (2,438 to 3,048 m). Interconnected valleys between the peaks are filled with glaciers and ice fields. These ice fields and smaller ones to the southeast feed many streams.

The climate of southeast Alaska is maritime, which means small temperature variations, high humidity, high precipitation, considerable cloudiness, little freezing weather, and an average temperature of around 40 degrees F (4 degrees C) and an average precipitation of well over 100 inches (254 cm) in much of the region. Temperatures vary little from place to place in southeast Alaska, but precipitation changes markedly depending on exposure to marine influences and altitude.

These cool, moist conditions produce a lush forest growth, which is an extension of the rain-belt forest of the Pacific Northwest. The forest is broken here and there by rain shadow areas, muskeg bogs, glacial outwash plains, and marshlands in river valleys and deltas.

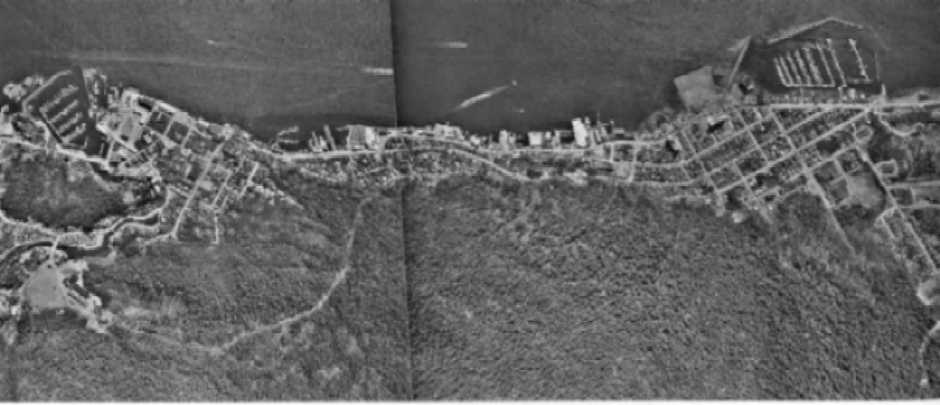

Juneau, the state capital with 13,556 people, is located in this region which contains 14 percent of the state's people. The next largest population centers are Ketchikan, Sitka, Petersburg, and Wrangell. Community development is hampered by steep topography and most settlements are located on narrow benches on the seacoast (Figure 56). Land surface transportation is very limited, and the Alaska Marine Highway System and air travel provide most of the access in and through this region.

Wind Channeling

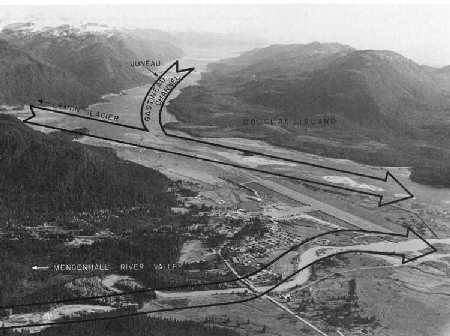

Wind speeds increase by channeling effects resulting from topographic features (Figure 16). Winds funneled through narrow valleys and mountain passes may increase drastically. Strong winds sweep snow off isolated exposed areas, permanently bend trees away from the direction of the prevailing wind, and occasionally keep an entire area free of large trees. Channeling is a common and powerful phenomenon along the Taku River and Inlet and the Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau. Channeling can change the direction of prevailing winds.

Figure 16

Wind Channeling

| Air funneled through the Gastineau Channel converges with that originating over the Lemon Glacier near the Juneau Airport in the center of the picture. Air off the Mendenhall Glacier flowing down the Mendenhall River valley is shown near the bottom. |

|

Winds channeled through the Taku River valley and inlet raise spray from the surface of the water to heights at times exceeding 300 feet. |

| Old Russian Orthodox Church at Juneau. Weather records here began in 1881. However, in Sitka they date back to 1842, well before Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867. |

Figure 44 Tide data for selected locations, Southeast region (719K) Oversize Document may take some time to load

Slope Maps

Slope is defined as the gradient of the land surface and is measured as percent, angle in degrees, or a ratio (Figure 59). Slope maps summarize slope information by grouping local areas with similar slope values into single map units. They are prepared from topographic maps, and greater detail is added from aerial photographs and field data. Used in conjunction with geology, vegetation, and soil maps, slope maps are valuable tools in evaluating such environmental factors as susceptibility to avalanches, rockslides and landslides, erosion, and flooding—all critical to safe development.

Because of the steep and rocky nature of the terrain in southeast Alaska, slope data must be given careful consideration before development. Most communities in Southeast are restricted by steep mountain slopes to narrow strips of land along the coast. Thin, coarse-grained soils inhibit growth of vegetation, and coupled with the steep grades, lead to snow avalanches, landslides, and related mass wasting phenomena. Figure 60 shows how topographic data can be interpreted to determine slope grades. The map is part of a study prepared by Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall (1972) for the Juneau area. This study investigates several engineering concerns, including seismic, mass wastage, and snow avalanche hazard areas.

| Steep topography has forced the development of Ketchikan in a linear pattern along the coast. |

| Residential development at the base of the mountains at Juneau may be affected by rockslides and avalanches. |

Figure 91

Summary of Metallic Mineral Activity by Mining District—Southeast Alaska

|

Mining District |

Commodities |

Claim Staking |

Placer Production |

Lode Production |

|

Yakutat |

Gold, titanium, copper |

Light, limited to the beaches |

Insignificant |

Insignificant |

|

Juneau |

Gold, zinc, lead, copper, silver, nickel, molybdenum, iron |

Widespread where rock crops out, especially around Juneau and Procupine Creek |

120,000 ounces of gold from Porcupine Creek |

6.75 million ounces lode gold from Juneau, Douglas, Berners Bay, Eagle River, Port Snettisham, and Reid Inlet |

|

Admiralty |

Gold, copper, nickel |

Moderate, concentrated at north end of Admiralty Island |

No recorded production |

43,000 ounces gold from Funter Bay/Hawk Inlet area |

|

Chichagof |

Gold, silver, copper, nickel, molybdenum, chromite |

Widespread, most intense along the northwest coast of Chichagof Island |

No recorded production |

Over 3/4 million ounces gold (some by-product silver) from Chichagof Mine and Hirst-Chichagof Mine; the Alaska Chichagof Co. mined at least 300 tons of gold—silver ore was another big producer; several other smaller prospects existed. A gold prospect on Yakobi Island reportedly yielded $1,000 in gold |

|

Petersburg |

Gold, zinc, lead, copper, silver |

Moderate, occurring mainly near beaches |

140 ounces recorded gold production from Windham Bay |

25,000 ounces gold plus some silver from northern part of district |

|

Kupreanof |

Gold, lead, zinc |

Moderate, limited to accessible areas near the beaches |

No recorded production |

Insignificant |

|

Ketchikan |

Copper, gold, silver, palladium, lead, zinc, uranium, iron, antimony, molybdenum, beryllium, thorium, chromite |

Intense on the islands within the district |

Insignificant |

Total production unknown; conservative estimates are 28 million pounds copper; 45,000 ounces of gold; 200,000 ounces of silver; 11,000 ounces of palladium; 74,819 pounds of zinc; 42,100 pounds of lead; and 115,000 tons of uranium ore. Kasaan Peninsula was a major producing area, along with Hetta Inlet. Uranium was mined at Bokan Mountain, Prince of Wales Island. |

|

Hyder |

Gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, tungsten |

Light, except in northern part of the district |

Insignificant |

Riverside Mine yielded about 3,000 ounces of gold; 100,000 ounces of silver; 100,000 pounds of copper; 250,000 pounds of lead; 20,000 pounds of zinc; and 70,000 pounds of tungsten oxide. |

|

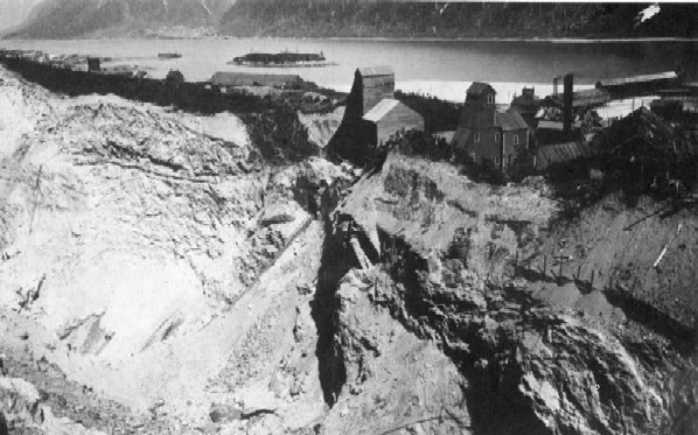

| The Treadwell Mine on Douglas Island was a major producer of gold until World War II. |

Water

The volume of water that falls as precipitation in southeast Alaska averages more than 100 inches a year for the region. Despite the amount, most of this precipitation runs off the land into lakes and streams as surface water, and only a small amount filters into deeper layers as groundwater.

The interrelationship of fresh water, surface water, groundwater, and the ocean systems—the hydrologic cycle—is shown in Figure 96. The earth's capacity to accept, store, and yield water depends on the type, size, number, and degree of interconnections that can store and conduct groundwater. The relative amount of water retained in, released to, or rejected from the ground depends on the nature and distribution of materials present in the shallow parts of the earth's crust.

Sand and gravel store large amounts of water and transmit it readily. These permeable deposits are referred to as groundwater aquifers. Clay may contain as much or more water per cubic foot than sand and gravel, but it holds water in such small pores that it cannot be transmitted to wells in usable quantities—it is impermeable. Compact bedrock that contains water only in fractures is also impermeable. Impermeable material acts as a barrier to water movement through the ground.

Although no permafrost exists at lower elevations, the region contains extensive glaciers. The winter snowpack accumulates precipitation which melts during spring and summer and adds water to the streams and lakes in the area. During extremely wet, cold years glaciers accumulate snow, which melts during the warm, dry years and maintains the streams and lakes throughout the area. Nearly all of this stored water flows directly into the streams and does not pass through the groundwater system because of a lack of aquifer storage.

The Malaspina Glacier, one of the largest ice masses in North America, lies in the extreme northwest of the region. It flows from the St. Elias Mountains, which range in elevation from 8,000 feet (2,438 m) to 19,000 feet (5,791 m). Interconnected valleys among the peaks are filled with glaciers and ice fields that compose this third largest glaciated area in the world. These ice fields and smaller ones to the southeast feed many streams of the region.

Surface water and groundwater contain mineral ions in solution as a balanced system of cations (positive ions) and anions (negative ions). The nature of these ions is determined by the mineral content and structure of geologic deposits scoured by flowing and percolating waters. Because health hazards are directly related to the chemical concentration of various ions, the U.S. Public Health Service established water quality standards for many uses in 1962. The Alaska Department of Health and Welfare adopted these standards in 1967, and the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation enforces them. Figure 97 shows water quality standards for drinking water.