THE MAN-MADE ENVIRONMENT

The People

History

Two groups of Indians, the Tlingits and Haidas, occupied southeastern Alaska at the time of initial European contact. The Tlingits pre-date the Haidas, who within historic times migrated from the Queen Charlotte Islands area below Dixon Entrance and occupied the southern portions of the Tlingit territory. In 1887 a group of Tsimshian Indians, led by the English missionary William Duncan, migrated from the Fort Simpson area in British Columbia to Port Chester on Annette Island and established the colony of Metlakatla. There was a broad range of similarities in lifestyles, customs, and habits among these groups, but the Tlingits have remained the dominant aboriginal group in southeast Alaska. Differences were principally conditioned by language and geographic location: some groups were oriented to the open sea while others adapted to life along the rivers and inland bays.

Archaeologists have practically ignored the prehistory of these aboriginal settlers, so almost no archaeological material is available to outline this stage of their cultural development. The first significant archaeological research in the region was carried out by Frederica de Laguna in the Alexander Archipelago and Yakutat Bay in 1949 (de Laguna 1960). She continued her work at Angoon in 1950 and at Yakutat during 1952-1954 (de Laguna et al. 1964). After a hiatus of almost a decade archaeological research in the region was resumed at Glacier Bay National Monument in 1963 by a Washington State University group led by R.E. Ackerman (Ackerman et al. 1965). Very few prehistoric sites have been positively identified and only one, the Ground Hog Bay Site No. 2, north of Hoonah across Icy Strait (Figure 141) which is still being investigated, has yielded substantive data.

Figure 141 Historical Patterns, Southeast region (722K) Oversize Document may take some time to load.

Three cultural layers have been identified at this site. The oldest produced two bifacial fragments, a scraper, and three flakes which have been radiocarbon dated to around 9,000-10,000 years ago. The middle layer contained a lithic assemblage of microblade cores, microblades, macrocores, flakes, choppers, various scraping and cutting tools as well as a complex zone of fire-cracked rocks, hearth areas, charcoal, burned bone, and cobbles to small boulders. This layer was radiocarbon dated to about 4,000-8,000 years ago. The youngest cultural layer is dated from about 350 years to around the historic period.

Riddell (1954) has theorized that the northern portion of Southeast, around the Gulf of Alaska and the Fairweather Range, was probably uninhabitable prior to 6,000-7,000 years ago because of glaciation, while the southern portion may have been open to human habitation several thousand years earlier. The Tlingit appear to be the last aboriginal group to migrate to and occupy Southeast before the arrival of white men. Clan legends suggest that this migration probably occurred about 1,500 years ago. Linguistic evidence indicates that the Tlingit people split off from the basic Na-Dene language family in interior Canada about 2,000 years ago and moved from the Interior to the coast along the Skeena, Nass, Taku, Stikine, and Alsek river valleys which penetrate the Coastal Range (Figure 141 ). After settling in Southeast, the riverine orientation shifted first to a beach culture phase, and then prior to European contact, emerged as a sea-going culture.

Reliable authorities estimate the precontact population of the Tlingit and Haida Indians in Southeast at about 10,000 people. Kroeber divided this figure into 2,500 inhabiting the more rugged northern half of the territory and 7,500 living in the southern regions. Lisianski, the Russian scholar who visited the region during 1803-1806, supported the 10,000 estimate. The Kaigini Haida on Prince of Wales Island were estimated at about 1,735 during 1836-1841 (Figure 142).

Figure 142

Estimated Distribution of Alaska Native Population by Cultural and Linguistic Classifications, 1740-1970

|

Circa 1740-80 |

Circa 1839-44 |

1880 |

1890 |

1910 |

1920 |

1929 |

1939 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

|||

|

Northwest Coast Indian |

11,800 |

8,300 |

8,510 |

5,463 |

5,685 |

5,261 |

5,895 |

6,179 |

7,300 |

7,900 |

8,300 |

||

|

Tlingit |

10,000 |

6,565 |

7,712 |

4,115 |

4,426 |

3,895 |

4,462 |

4,643 |

5,500 |

6,000 |

6,300 |

||

|

Haida |

1,800 |

1,735 |

798 |

395 |

530 |

524 |

588 |

655 |

750 |

800 |

800 |

||

|

Tsimshian |

953 |

729 |

842 |

845 |

881 |

1,050 |

1,100 |

1,200 |

|||||

|

Northern Athapascan Indiana |

6,900 |

4,000 |

4,057 |

3,520 |

3,916 |

4,657 |

4,935 |

4,671 |

5,100 |

6,500 |

8,300 |

||

|

Interior (Ingalik, Koyukan, Tanana, Kutchin) |

4,800 |

2,100 |

3,193 |

2,531 |

2,922 |

3,657 |

3,935 |

3,671 |

3,900 |

5,000 |

6,400 |

||

|

Pacific (Eyak, Athena, Tanaina) |

2,100 |

1,900 |

864 |

989 |

994 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,000 |

1,200 |

1,500 |

1,900 |

||

|

Western Eskimo |

26,600 |

24,500 |

17,617 |

13,871 |

15,279 |

14,990 |

17,171 |

19,169 |

19,320 |

24,800 |

31,400 |

||

|

Inupik (Arctic) |

6,350 |

6,000 |

3,492 |

2,336 |

3,305 |

3,487 |

4,227 |

5,489 |

5,600 |

6,200 |

8,060 |

||

|

Yupik |

|||||||||||||

|

Siberian (St. Lawrence) |

600 |

600 |

500 |

267 |

292 |

300 |

389 |

505 |

540 |

636 |

785 |

||

|

Cux (Nunivak) |

400 |

400 |

408 |

373 |

301 |

184 |

181 |

215 |

203 |

232 |

258 |

||

|

Yuk (Bering Sea) |

10,550 |

10,000 |

9,702 |

8,734 |

8,502 |

8,313 |

10,184 |

10,414 |

10,617 |

15,232 |

18,397 |

||

|

Suk (Pacific)b |

8,700 |

7,500 |

2,242 |

2,161 |

2,879 |

2,706 |

2,190 |

2,546 |

2,360 |

2,500 |

3,900 |

||

|

Aleutc |

12,000 |

2,200 |

2,628 |

1,679 |

1,451 |

1,650 |

1,857 |

2,006 |

2,180 |

2,800 |

3,100 |

||

|

Unclassified |

184 |

821 |

125 |

433 |

|||||||||

|

TOTAL ALASKA NATIVE |

57,300 |

39,000 |

32,996 |

25,354 |

25,331 |

26,558 |

29,983 |

32,458 |

33,900 |

42,000 |

51,100 |

||

a Division by Interior and Pacific Athapaskin estimated for 1920, 1929, and 1939.

b Identified as "Aleut" in recent census and other reports. Belong to Konaig (Kodiak Island) and Chugach (Prince William Sound). Classified by Oswalt as Pacific (Suk) dialect of Yupik.

c 1920-1950 classified by location. 1960-1970 includes estimates of urban and relocated Aleuts.

Source: G.W. Rogers, 1971. Alaska Native Population Trends and Vital Statistics, 1950-1985.

The settlement patterns of the Tlingit and Haida were strongly influenced by the great variety and number of natural resources of both land and sea. The Tlingit and Haida established two basic types of settlement: permanent winter villages and temporary summer villages close to their fishing and hunting grounds. Permanent villages were usually located on the narrow sand beaches of bays, inlets, and lower river courses with the forest behind and a good view of the water approaches to the village. Both Aurel Krause, the German ethnologist, and Ivan Petroff, a Census Bureau official, commented on aboriginal summer nomadism:

Like all the inhabitants of the Northwest Coast, the Tlingit are a sedentary people. In the summer, however, they lead a nomadic life, for they scatter according to clan and family lines to their hunting and fishing territories, or undertake extensive voyages, which sometimes last for months in order to trade with whites or neighboring Indians (Krause 1880).

The Thlinket, like most of the tribes of the northwest coast of North America, may be called marine nomads, as they occupy fixed dwelling places only during the winter, roving about during the summer in search of food for the winter (Petroff 1880).

Villages varied in size from a few houses to settlements of 50 or more houses spaced about 50 to 100 feet apart :in ordered rows. Lisianski, the Russian explorer, commented on the houses in the winter villages:

The barabaras of the Sitkan people are of a square form, and spacious. The sides are of planks; and the roof resembles that of a Russian house, except that it has an opening all along the top, of the breadth of about two feet, to let out the smoke. They have no windows; and the doors are very low to enter. In the middle of the building is a large square hole, in which fire is made. In the houses of the wealthy, this fire-place is fenced round with boards; and the space between the fire-place and the walls partitioned by curtains for the different families of relations, who live together in the same house. Broad shelves are likewise fixed to the sides of the room for domestic purposes.

Each Indian group of Southeast had characteristics similar to individual nations. They had a common language, name, and set of customs. Each "nation" was divided into two groups called phratries, each with its own totemic system. These phratries were essentially ceremonial and consisted of clans whose members could not intermarry. Among the Tlingit there were two principal phratries: the Raven, most common in the south, and the Wolf (sometimes referred to as the Eagle) in the north. Similarly among the Haida there was an Eagle and a Raven phratry.

A number of clans were in each phratry. Authorities differ as to the precise number of active clans among the Tlingit, but there seems to have been about 15 at the time of Russian contact in 1741, each established within more or less clearly defined geographic boundaries (Figure 141). The Haida clans were far less numerous.

Local clan division was the primary owning, organizational, and management group. Clan membership established the relationship of an individual to clan property. Property rights were only protected to the extent that the clan stood behind them. All clan members were bound by common consent to defend clan property against outsiders, share the use of their property among themselves, and enforce the rules established by tradition and economic necessity. Traditionally, clan property consisted of salmon streams, berry patches, sealing rocks, house sites in the villages, and in some instances trade trails into the interior, hunting grounds which usually consisted of the watersheds of streams or valleys, and well-defined tracts of open sea such as halibut banks located by lines of sight on prominent landmarks. As de Laguna stated in 1973:

If our picture of the world is that of the farmer, property owner and landlubber, the Tlingit's is that of the traveler, especially the mariner, who is concerned with places and the routes between them. The world for the Tlingit is probably visualized more as it is in our sailing and harbor charts than as it is in our political areal maps, for such charts reduce the land to landfalls, to reefs, shoals, and anchorages to be avoided or sought and they sacrifice or distort lineal and area measurements to emphasize angles or direction. Sib territorial rights do not refer then to areas but to specific spots: fishing streams, coves, berry patches, or house sites, etc., and the terrain or water between these places are simply the relatively undifferentiated landscape through which one travels in going from one to the other.

Each clan was based on maternal descent and consisted of a group of brothers and their male cousins who, together with their families, lived in one or more houses depending on their number. The minimal political and social unit of the Haida, Tlingit, and the Tsimshian was the local house group. Each village had its highest ranking house, the chief of which, usually the eldest brother of the group, was recognized as the highest ranking local clan chief. Marriage within the clan or phratry was forbidden, so villages were usually comprised of two or more local clans from opposite phratries.

The house groups were generally, but not always, cohesive units held together by the fundamental principles of common social identity, ownership, enterprise, inheritance, and leadership (Lisianski 1804). The house itself, slaves, large canoes, important arms, trade goods, and many of the utensils as well as noneconomic property such as totem poles, house crests, dances, and ceremonial objects were the common property of the house group. There was, however, a great deal of individual property in the form of hides and pelts which the men of the house group accumulated for themselves by their own individual effort. The important economic activities of salmon fishing, oil making, berry picking, hunting, and trading were performed jointly.

The house chief in both societies was pre-eminently a ceremonial leader, a repository of myth and social usage, and an educator of the young men of the house group. He was primarily responsible for the trading activities of the group and the symbol of house group solidarity. As such, he represented the group in clan councils. In feuds or minor disputes he held the group in a solid front against all external infringements. The house chief decided when the seasonal fishing should begin and directed the work of slaves and of poor men without relatives.

Very small groups which settled in unoccupied places and built one or two houses were the basis of Haida and Tlingit villages. Among the Haida the first settlers established rights to ownership of economically strategic resources within the reach of the village, developed political leadership beyond that of the house chiefs, and recognized "village masters." The Tlingit did not develop similar leadership, and their villages appeared to consist of autonomous house groups presided over by independent house chiefs or "yitsati."

Traditionally, rights to territory that were properly validated in potlatches were inalienable. However, there are reports that such property sometimes changed hands. The Taku Tlingit are reported to have rented their fishing rights to other clans. Failure to use an area was regarded as abandonment and justified occupation by new claimants.

It appears that territory was sometimes acquired by conquest, and it is quite likely that the southeast Indians with their highly developed notions of property and indemnity were prepared to defend their property rights with their lives and to exact just retribution for trespass. Oberg (1973) pointed out that offenses against the life, property, and honor of a Tlingit were settled by a payment of goods and that such indemnities constituted an important form of wealth.

The economic year of the southeast Indians was based on the seasonality of resources. As spring approached, canoes were hauled from winter storage, their bottoms cleaned of slivers with a pine torch, and fishing and hunting gear prepared.

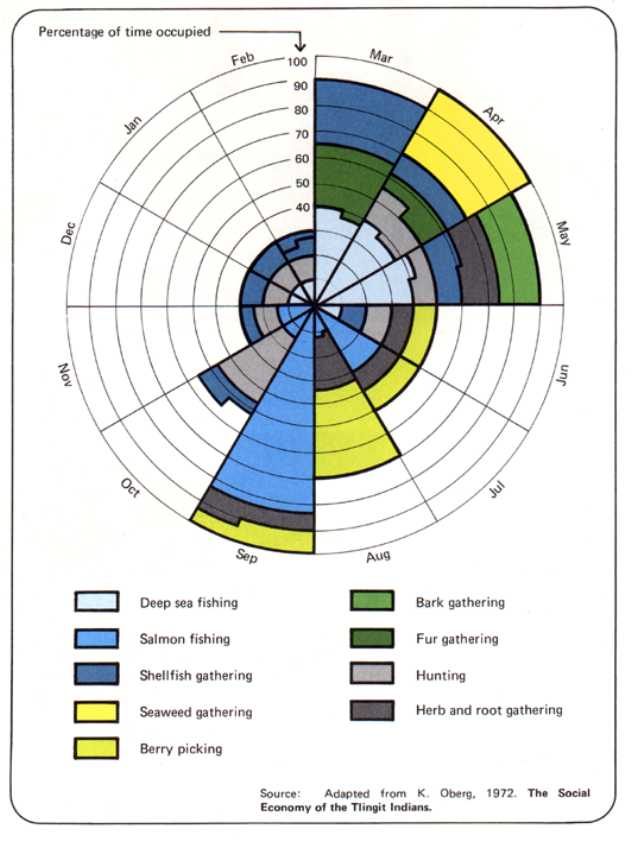

Figure 143

The Tlingit Economic Year

The eulachon (candlefish) runs began in February or March. Eulachon were highly prized for their valuable oil which was stored and used year-round. Also, in March halibut and cod were caught off the coastal islands, while on the mainland trout fishing predominated. Halibut, though secondary to salmon, was a major protein source in Southeast and was eaten in immense quantities. Traditional halibut fishing gear consisted of wooden hooks tipped by a bone barb attached to rawhide cedar bark or kelp lines. The fishing rig was particularly ingenious for it allowed the Indian fisherman to protect his bait from "trash fish" such as sculpin and rock fish for only the flat-headed halibut or flounder could get at the bait. So effective was this gear that even after the advent of the European, it continued to be used, modified only by the substitution of iron tips for bone.

Trout were taken with gill nets of rawhide or cedar bark twine that were drifted downstream by two men in a canoe, one paddling and the other retrieving the net. Great quantities of trout, particularly Dolly Varden, rainbows, and cut-throat, were taken this way, and in early spring catches were generally eaten fresh.

Throughout March a variety of clams, crabs, mussels, cockles, and snails and several types of seaweed were gathered. Throughout most of April, deep-sea fish continued to be taken, and sea mammals were hunted to supplement the fish diet. Sea otters were generally available in the inner bays of the Tlingit territory and were highly prized for their pelts, a valuable trade item. Seals were harpooned by hunters in light canoes in the shallow coastal waters, but whaling was never important among southeast Indians except the Yakutat Tlingit.

Cranes, ducks, geese, grouse, gulls, kittiwakes, ptarmigan, and swans and their eggs were taken. However, while birds and eggs were relished, they were never of major importance in the southeast Alaskan Indian diet. A variety of grasses, roots, and weeds useful as food, medicine, and fiber was collected and stored for later use. The tender stems of the salmonberry, wild rhubarb, wild clover, and peas of the purple vetch were collected and eaten. The bark of the hemlock was peeled off and the soft white cambium layer was scraped off, cooked, pressed into cakes, and stored in boxes for winter use.

Herring swarmed into the mouths of numerous coastal rivers in May, attracting in their wake porpoises, whales, and seals as well as many kinds of fish. Herring was harvested, principally for roe and oil, with a herring rake, dip baskets and nets, dragging nets, or simply by a jigging line set with several hooks. De Laguna reported that in the old days: "Schools of herring used to crowd so tightly into the bays that a strong arm was needed to drive the fish rake through the mass of their bodies."

Trade was an important part of the economic and social life of aboriginal southeast Indian groups, and most was conducted in late spring. The regional distribution of resources resulted in regional specialization of production and in regional interdependence.

... we can see it even today in the household possessions of the Tlingit, which are the products of many different places. The caribou skin which the Chilkat use for their clothing, the sinew with which they sew, the lichen with which they dye their dancing blankets are all secured through trade with the Athapascan-speaking Indians of the interior. The dentalium, the sharks' teeth and pieces of mother of pearl. . . which they wear as jewelry in their ears or hang as pendants, on a thong around the neck come from the south, principally from the Queen Charlotte Islands. (Krause 1880)

Trade was usually conducted in well-established patterns between trade partners who generally were either actually or quasi-related. Each group established monopoly over specific trade routes and spheres of influence which they jealously guarded. The Wrangell clans are reported to have held trading rights with the Athapascans at the headwaters of the Stikine River, while the Taku people on the Taku River and the Chilkat on the Chilkat River exercised similar monopolies. This monopoly of specific trading areas and routes was so strong that it became one of the major areas of friction between American traders and Indian groups during the late eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth centuries. The Hudson's Bay Company established a trading post about 1854 in the Yukon Valley, which the Chilkats marched inland and destroyed.

The major river systems of the Yukon and the Mackenzie were navigable and provided a conduit to the Interior. The Chilkat, Stikine, and Taku actively traded with interior Natives along these "grease trails," so-called because the primary trade article was candlefish oil. From the Interior the coastal people obtained prepared moose hides, dried meats, jade tools, copper, highly decorated moccasins, birch bows wound with porcupine gut, and prepared caribou hides. The hides were highly valued for making shirts and trousers. Thongs and sinews of various kinds were traded by the interior people for cedar bark, baskets, fish oil, iron, shell ornaments, and plates of copper.

|

The Tlingit often traded far south

into Haida and Tsimshian territory where they exchanged hides, Chilkat

blankets, and copper for the large cedar canoes typically of Haida manufacture.

The same articles were also traded for slaves, since the latter group

generally owned large numbers of slaves secured in raids against the Salish

in British Columbia.

|

| Chilkat blanket |

Trade as well as many other aspects of the economic life in Southeast depended on water transportation, and for this the dugout canoes of the region played an essential role. The elaborate woodworking process covered not only boat building but almost every other aspect of southeast and northwest Pacific Coast aboriginal cultures. Some woodcrafted articles were used only on rare and ceremonial occasions, while others were in everyday household use. Wooden chests, serving dishes and trays, cooking and storage boxes, spoons, fish hooks, and clubs provided outlets for the artistic expression of the woodcarver. While wood was the basic material used, highly ornamented articles of bone, horn, and ivory were also produced. In precontact days all wood was worked with bone and stone tools and with fire. Almost every wooden item possessed by Tlingit, Haida, or Tsimshian had some form of totemic creature carved or painted on it.

Art style is the distinguishing feature of any people, and this is emphatically true for southeast Alaska Indians. As noted Alaskan economist George Rogers (1960) stated: "it was in this area that concepts of hereditary status and wealth held sway and where potlatch and secret society performances provided ample opportunity for the skill in making of decorated articles." Color was extensively used to emphasize or further describe the separate parts or details of a carving. Totem poles and masks are the most widely known forms of southeast art. Models of this art form were reconstructed during the 1930s and have been preserved at Saxman Totem Park and Totem Bight Park, both near Ketchikan.

By late June trading was completed, and summer fishing villages were established on the salmon streams. The timbers that had been prepared during winter were used to make summer houses, and preparations were made for the runs of the salmon in the bays and rivers of the region. Traditionally, the first runs were not as intensely harvested as later runs. The Indians principally occupied themselves with collecting fresh salmon roe.

The roe of fish is esteemed a great delicacy, and great care is taken to collect it in the water, or remove it from captured fish. It is either eaten fresh, or dried and preserved for winter's use, when it is eaten in two ways: 1) It is pounded between two stones, diluted with water, and beaten with wooden spoons into a creamy consistence; or 2) it is boiled with sorrel and different dried berries and molded in wooden frames into cakes about 12 inches square and one inch thick . . . Dried fish, bark, roe, etc. are eaten with grease or oil . . . salmon roe is buried in boxes on the beach washed by the tide, and eaten in a decomposed state. (Niblack 1970)

Berries were the most important plant food, and berrying began in earnest in August. Excursions to berrying patches were social affairs which usually involved the whole family. Women and children were primarily responsible for this activity, although several men generally guarded against bears and carried the huge berry baskets back and forth to the canoes. Blueberries, highbush cranberries, red elderberries, salmonberries, gooseberries, wild currants, lowbush cranberries, and strawberries were harvested.

Traditionally, the major hunting season for land animals in Southeast began in early fall. The most important prey were bear and mountain goat. They were hunted during late August through fall and early winter when the animals were fat. Bows and arrows were the traditional hunting weapons for mountain goats, whose fat was highly prized. Their horns were used for making spoons, and after the introduction of firearms, for powder measures. Black bears were hunted with spears, but more often dropped in deadfalls, and their meat eaten fresh or dried. In addition foxes, mountain sheep, porcupine, marmot, otter, mink, beaver, squirrel, lynx, marten, rabbit, weasel, wolf, muskrat, and raccoon were hunted.

September was the most economically important month of the year, for this was when salmon fishing began in earnest. Each house group "owned" its own particular salmon stream or section and jealously guarded it against trespass. The spear appears to have been the most common way to catch the larger salmon, particularly the king.

|

Much of the subject matter of southeast Native artists was drawn from clan legends, quasihistoric events, and tribal myths of the creation. The goal of the artist was to tell a story and to illustrate participants and events so that they would be immediately recognized by those familiar with the tale. Supernatural human and animal "heroes" challenged the ingenuity of the artists and helped to produce an art noted for its distinctive symbolism. For example, the shape of the beak indicated particular birds, fin and tail shapes distinguished sea mammals and fish, and heads and tails differentiated land animals. Ordinary people were depicted with regular, though often exaggerated, features.

|

|

Saxman, 1938 |

|

There were at least two types of fish traps in use before contact with Europeans. The more common was the cylindrical trap made of split sticks of red cedar lashed to hoops with spruce roots. This basket-like trap had an opening which was just large enough to allow the fish to enter but not find its way out. The second type of trap was a much larger fence-like affair made of red cedar or other local wood, built across a major river and staked to the river bed. An inner part of the trap prevented the fish from escaping. Salmon were allowed to enter the river upstream of the trap and then driven downstream into the trap from which they were then removed. Besides the various traps and spears, other gear such as gaff hooks were used in silt-laden water. |

| Gaff hook carved and painted

by Harry K. Bremner in 1954 to represent a killer whale. The human face in the blowhole probably symbolizes its spirit (qwani). |

After the fall fishing season, the people moved back to their permanent winter villages and resumed the traditional round of basket and blanket making, house building, and other ceremonial and social activities such as the potlatch. This complex part of southeastern aboriginal culture combined concepts of acquisitiveness, property, and competition.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries a world-wide curiosity speculated on the whereabouts of the western opening of the Northwest Passage and whether Asia and North America were joined somewhere in the Arctic. The question of a continental connection inspired a series of Russian voyages between 1725 and 1741 led principally by a Dane, Vitus Bering.

Bering made his last voyage in 1741 with Alexei Chirikov, and it was to have important consequences for southeast Alaska. They sailed from Petropavlovsk-on-Kamchatka and made the first recorded European landfalls on the southeast Alaska coast at Cape St. Elias on July 17, 1741. Georg Wilhelm Steller, a German naturalist, accompanied Bering on the St. Peter and explored Native houses on southern Kayak Island and recorded observations of the flora and fauna in the region. Fleet Master Sofron Khitrov made similar explorations on Wingham Island, but none of Bering's crew reported sighting Alaska Natives. Chirikov commanded the St. Paul, the second ship of the expedition, and landed somewhere in the vicinity of Cape Edgecumbe and coasted north to Chichagof Island where he encountered hostile Tlingits.

Chirikov returned safely to Russia, but Bering was shipwrecked and died of scurvy on one of the Commander Islands. The survivors of Bering's crew killed and skinned hundreds of sea otters and returned to Siberia with the valuable pelts. The expedition produced a tentative answer to the question of continental connection, but clarification had to wait until Captain Cook charted Bering Strait in 1778.

The Russians, meanwhile, were far more eager to exploit the fur resources of the Aleutians. The year after Bering's 1741 expedition returned, Emelian Basov sailed to the island where Bering died and verified the presence of thousands of sea otters in the eastern ocean. For the next 56 years, 1743-1799, the search for richer fur-hunting grounds was the major impetus to the Russians' movement across the Aleutians and along the Gulf of Alaska to the Alexander Archipelago.

Most of these ventures originated from the Siberian ports of Okhotsk or Petropavlosk and were financed by Siberian merchants like Gregor Shelekhov, whose company would establish the first permanent settlement at Kodiak and later evolve into the government-sponsored monopoly called the Russian-American Company. The Russian-American Company became, in effect, the legitimate representative of the Russian authority in America. Alexander Baranov was appointed as the first governor of the company and its territories.

Between 1774 and 1791 the Spanish, fearful of losing their Pacific domain, sent explorers up the coast where they briefly held Nootka Sound. Between 1785 and 1800 many English, French, Russian, and American ships explored the coastal areas of Southeast. Some of these explorers, like Cook in 1776 and Vancouver in 1792-94, headed expeditions that were primarily exploratory, but most were primarily interested in expanding their nation's fur-trading operations. In the 1790s as many as 20 to 30 ships a year anchored at Nootka Sound, Parry Passage at the north end of Graham Island, and Cordova Bay across from Dixon's Entrance.

As competition in the sea otter trade became keener, exploration of the more northerly areas increased, and the Tlingit and Haida were drawn gradually into the commercial fur trade. Many crews traded directly with the aboriginal inhabitants in their summer camps during the annual harvest of salmon and other fish and seafood resources. Most of these expeditions included clerics, naturalists, geographers, cartographers, and artists, and much of our present information concerning the life of Southeast's aboriginal inhabitants is owed to these men.

The Russians continued to move west, searching primarily for new sea otter hunting grounds, although the dense stands of hemlock and spruce in southeast Alaska were also attractive to them. The first organized movement into Southeast was undertaken in 1788 by Sturman Ismailof and the Cossack Bocharof who, with a large hunting force, penetrated as far as Yakutat and Lituya Bays. In 1795 Baranov led another large band of hunters into the Lynn Canal area, home of the aggressive Chilkat Tlingits. In 1796 Baranov sent a group of about 30 Russian families from Kodiak to Yakutat Bay to establish an agricultural colony to counter the growing influence of British and Yankee traders in the area. The settlement did not prosper. They quarreled among themselves and had poor relations with the Natives. During the first winter 30 of the settlers died of scurvy, and the community's importance dwindled.

Baranov turned his attention to securing a Russian foothold on Sitka. In 1799 he led a large group of Russian and Native hunters to Sitka Sound, where after apparently friendly negotiations with the Sitka Tlingit, a small fort named the Redoubt Archangel Michael was established. When Baranov returned to Kodiak, instructions from the company to move their headquarters to the new fort on Baranof Island awaited him. The promise of new sea otter hunting grounds, unlimited timber, and good harbor inspired Baranov to comply rather enthusiastically with the directive.

The Russians who had remained at the new settlement were having second thoughts. They had misjudged the hostility of the Sitka Tlingits, whom they had outraged by seizing hostages. In June 1802 the Tlingit attacked the Redoubt Archangel Michael and destroyed it, killing all the inhabitants but a few who were rescued and returned to Kodiak by an English trader. De Laguna reports that most of the Tlingit tribes in the area probably took part in the attack, and they might have been assisted by English and American seamen who had jumped ship or been marooned at Sitka in 1799. It has further been claimed that British traders may have incited the Indians in hopes of eliminating Russian competition.

Baranov was not deterred. In 1804 he sailed into Sitka Sound with a force of 120 Russians and about 800 Aleuts. The Sitka Tlingit had abandoned their town of Sitca and built a new fortified town at the mouth of the Indian River. Baranov's force occupied Sitca in September 1804, renaming it New Archangel. With the aid of several Russian naval vessels, commanded by Captain Urey Lisianski, he mounted an eight-day siege of the Indian River fort. New Archangel, present-day Sitka, became the new headquarters for the Russian-American Company.

The Russian hold on southeast Alaska was rather tenuous, and their settlements had to be heavily guarded. The Tlingit's dominance, reinforced by the willingness of most non-Russian traders to let them retain their traditional autonomy, was based in part on their ability with firearms. Spears and arrows, according to Lisianski were almost a thing of the past by 1805.

Russian control in southeast Alaska was being challenged in the early 1820s. In 1825, a Russian-British convention defined their territories and established the Russian-American southern boundary at latitude 54.40. This boundary was violated by the Hudson's Bay Company, but a direct confrontation over British rights to establish a trading post on the Stikine River near present-day Wrangell resulted in a settlement between the two governments whereby the Hudson's Bay Company gained control over a large area of southeastern Alaska until the American purchase.

A terrible smallpox epidemic spread from California to Alaska, appearing first at Sitka in 1836. In the village near the Russian fort 400 Natives died within three months, representing almost half of the population. Angoon suffered severely, as did villages between Yakutat and Dry Bay. Veniaminov, the Russian cleric, estimated that by 1840 there were less than 6,000 Kolosh (Russian for Natives in southeast Alaska) whereas in 1833 there had been as many as 10,000.

During the decade of the 1840s, southeast Alaska served as a center of important industrial and fur-trading activities. Sitka flourished briefly as a shipbuilding center during the 1840s to 1850s. The industry did not last long, however, for more seaworthy ships were built for less in British and American shipyards. Nonetheless, shipbuilding stimulated Russian interest in supplying coal for the new steamships.

With the fur trade in serious decline, the Russians felt that developing the mineral resources of the region might enable them to hold on to their American possession. Accordingly, in 1849 Peter Doroshin, a graduate of the Imperial Mining School at St. Petersburg, was commissioned to study the mineral potential of the colony. He located coal deposits at Port Graham on the Cook Inlet but was prevented from good prospecting in Southeast because of Hudson's Bay Company control of the then-unknown gold-bearing belt.

Through the 1850s southeastern Alaska, and Sitka particularly, enjoyed something of a gracious age. Commerce resulting from the Pacific tea trade kept the economy going. Whaling was attempted with only moderate success on the Fairweather grounds, but other industries developed in the little town of 1,278 people. The influx of gold seekers into California provided the Sitka Company with a market for ice, and for several years tons of ice were shipped from Southeast to San Francisco at about 25 dollars a ton. That trade was soon lost to Southeast when the company moved its ice operations to Kodiak. The Russian search for minerals never resulted in substantial enterprise.

Baranov Castle, the official home of the Russian governors, was built in the decade starting in 1826 and provided the setting for a frontier facsimile of St. Petersburg court life. A succession of gracious Russian women, among them Baroness von Wrangel, Lady Etolin, and Princess Maksoutoff, helped to make frontier life less elemental. The company opened a Colonial Academy at Sitka where young Russians and some creoles were trained as surveyors, navigators, engravers, and accountants. Much of the work for Tebenkov's Atlas of Alaska was done by young men trained at the Sitka Academy. Lady Etolin established a school for young ladies where they were taught the essentials of good breeding. A theological school, later upgraded to a seminary, was established in Sitka in 1841, but it only operated for a short time. Several notable clerics worked in Southeast, among them the indomitable Father Veniaminov, who came to Sitka in 1834 and in subsequent years wrote a treatise on the Tlingits.

Despite this flicker of gentility in Southeast, it became evident by the late 1850s that Russia's hold on its American possessions was definitely waning. Blocked from exploiting new lands to the south and east, while their own fur resources continued to decline, the Russians faced serious economic difficulties compounded by the geopolitical ambitions of the British. Perhaps the statement of the Russian Minister of State Property in 1862 best summarizes the situation:

The main pursuit of the colonies—the hunting of sea otter—has been gradually on the decline. Generally speaking, the fur business has begun to yield first place to Canada and Great Britain. Whaling in the colonies has passed into the hand of the Americans. Fishing has been done on a scale which barely meets the needs of the colonies themselves . . . Nothing has been done with respect to farming and cattle breeding. The mineral resources of the region have hardly been tapped; the commercial relations that the Company has maintained have been seriously impaired and are falling into decay, its merchant marine has been allowed to be reduced to negligible proportions, and it is compelled to charter foreign boats to meet its own requirements.

The unilateral Russian attempt at penetration and domination of the Tlingit was, for the most part, ineffective. The Tlingits' culturally unified view of themselves inhibited any massive onslaught on traditional Native ways and customs. In 1867 Russia sold its American possessions to the United States for $7.2 million. Despite Tlingit claims that all the Russians were entitled to sell were the lands on which their installations stood or lands they actually controlled, all land and other property passed to the United States government.

On October 18, 1867, General L.H. Rousseau, escorted by a small contingent of U.S. soldiers from the ninth infantry, officiated at the transfer of the Russian possessions to the United States. The Tlingit were introduced to a new political order, in which the only law was that of armed soldiers who were often busily breaking the law themselves, and a new economic and social order in which money was the primary medium of exchange. The ancient trading system with all its rich complexities was quickly outmoded. Alaska became, in effect, a military outpost of the federal government.

For some months after the change in ownership, Sitka enjoyed a boom. Opportunists of all kinds, from preachers to prostitutes, headed north with their dreams. Between 1867 and 1869 some 70 ships crowded into Sitka harbor from San Francisco, British Columbia, Hawaii, Asia, and Russia and returned to West Coast ports bearing sheathing and bar metal, lead, bales of furs, and other sundries from the dismantled Russian installations.

The first years of American control were extremely disorganized with neither effective civil nor military government. Between 1867 and 1884 Alaska was ruled by officials of the War, Treasury, and Navy Departments. Only two substantive laws were enacted with regard to Alaska; one created a customs district in Alaska and the other turned over the Pribilof sealing grounds as a monopoly to a private San Francisco company. For 17 years it was not legally possible in Alaska to get married, obtain land title other than to small tracts deeded to the Russians at the time of the purchase or by special Act of Congress, bequeath property, or collect debts. Some local efforts were made to bring a semblance of control to southeast affairs. Within 30 days of the transfer, a town meeting in Sitka framed a charter, elected a mayor and council, and drew up city ordinances.

Despite official neglect, various scientific expeditions were sent to investigate the area's resources, survey coastlines, and harbors, and generally to collect data which might be useful in developing the new possession. One of the most significant of these expeditions was that of Ensign A.P. Niblack who gathered information in the summers of 1885-1887. He made photographic studies of the Haida but did not reach northern Tlingit settlements. Other quasi-governmental and private officials made studies of the Tlingit and Haida. Among the most useful are those of W.H. Dall, Ivan Petroff, Lt. W.R. Abercrombie of the Second U.S. Infantry, and the Harriman Expedition of 1899.

The year 1878 marks a turning point in the American period of southeast Alaska, for in that year the first commercial cannery was established at Klawock on Prince of Wales Island and a second at Sitka. The first full-fledged gold mining camp was established at Windham Bay. The gold discovered in the Cassiar District of British Columbia in the 1870s led to prospecting in the Stikine River valley, and Wrangell became a boom town. Prospectors spread from the Stikine and Cassiar Districts into the Alexander Archipelago and the neighboring mainland.

George Pilz, a German mining engineer who had come to Sitka in 1877, together with N.A. Fuller, a merchant, grubstaked prospectors who worked the coastal areas and offshore islands of Southeast in response to Auk Tlingit reports of gold found in the Gastineau Channel. Pilz and Fuller contracted with Richard Harris and Joseph Juneau, two miners who had worked in the Stikine and Cassiar fields, to prospect the coastal areas of northern Southeast.

After several months of poor luck, Juneau and Harris struck gold-bearing quartz along Gastineau Channel near the present state capital of Juneau. News of this find led directly to the founding of the city of Juneau as miners flocked to the new bonanza. Commander Henry Glass went to the new gold site and established naval barracks, the Northwest Trading Company sent Edward DeGroff to the area with supplies to open a store, a new customs house was established, and a post office called Harrisburg was created.

In 1882 French Canadian miner Pierre Erussard found placer gold on Douglas Island opposite the new town of Harrisburg. This new find gave rise to the twin city of Douglas, officially founded in 1887. Shortly after Erussard's discovery a California mining magnate, John Treadwell, bought out Erussard. The Treadwell mines produced over a half-million dollars in gold in a very short time. Meanwhile, a controversy developed over the name of the mainland city. Another American city was also called Harrisburg, and eventually the name of the Alaskan city was changed to Juneau.

The founding of the twin cities of Juneau and Douglas gave rise to several short-lived mining center satellites: Perseverance, Treadwell, and Thane. Ketchikan began with the establishment of a salmon cannery in 1886 and saltery in 1888. Fishing continued to be the mainstay of Ketchikan until it was eclipsed by the timber industry in 1955. Skagway was the product of the Klondike gold rush of 1897, and during its early years was principally a transportation center to the Yukon gold fields. The town of Petersburg also appeared in 1897 as a fishing and canning center. In 1900 Juneau replaced Sitka as the territorial capital. Craig was founded in 1907 as a salmon canning and cold storage site and became a permanent center with a customs house and small logging and other fishing industries. In 1908 Fort Seward, later named Chilkoot Barracks, was established in the vicinity of Haines and was maintained as an army post before being sold as surplus after World War II. It is now known as Port Chilkoot.

For the most part, the Natives of Southeast retained their tribal subdivisions and maintained their integrity. Some Tlingits gradually gathered around Sitka and Wrangell, while Indians from the Auk territory were attracted to Juneau. Only six of the original precontact Tlingit settlements remain today: Yakutat, Klukwan, Hoonah, Angoon, Kake, and Klawock. The village of Saxman near Ketchikan, founded by the remnants of the Cape Fox people, is essentially an aboriginal village, but was established under missionary influence. The only Haida settlement remaining today is Hydaburg. Metlakatla was established under missionary influence in 1887 and is the only active Tsimshian community.

News of the scenic grandeur of Southeast was circulated in the Pacific Coast press, and tourist excursions to the area were initiated by the Pacific Coast Steamship Company in 1884. By 1889 five thousand tourists were visiting Southeast annually. These visitors avidly bought Native handicrafts, often paying as much as $50 to $100 for furs and Native curios. The missionaries encouraged this trade since these articles were usually connected with Native religious practice. Reportedly, by 1890 most of the original Tlingit artifacts were sold off, and the Indians had started a handicraft industry.

It is important to keep in mind that the history of Southeast is, in many ways, coterminous with the history of Alaska. Southeast was home to one of Alaska's most remarkable aboriginal complexes, the site of much of the Russian activity in the state, and the region where American control was established and then expanded and consolidated over the territory's vast resources. The people and events that shaped Alaska's future also profoundly affected Southeast, and the dynamic drive for greater civil, political, and economic freedoms in Alaska reflect how closely the history of the region intertwines with that of the state.

Pressure for more effective government continued to increase. The powerful Presbyterian missions and their energetic leader, Sheldon Jackson, accelerated this demand. A forceful public speaker, Jackson played an important role in awakening Americans to Alaska's needs. His major interest was education of Alaska's Natives, but in his fight for Native rights, he allied his cause with the struggle for better government. His talents served the territory well for many years.

Disputes over landholdings and mining rights and conflicts between civilians and army officers over mining claims led to the declaration of martial law in the area in 1881 and a meeting in Juneau to which miners from all over Southeast were invited. The miners decided to send Colonel Mottram Ball as a delegate to the 47th Congress with a petition asking for representation. He was refused a seat and the petition was shelved, but Ball was treated respectfully and Congress even appropriated some money for his expenses.

In 1884 Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana, fortified by the presence of Jackson who had taken up residence in Washington, D.C., for the duration, sponsored the first Organic Act, officially designated "An Act Providing a Civil Government for Alaska." This bill, signed into law on May 17, 1884, provided for the regulation and administration of justice in Alaska but did not include legislative privileges to the territory. It provided for a presidentially appointed governor, created a district court with judge, clerk, district attorney, marshal, and four commissioners to handle minor legal matters. The court held two sessions a year, one in Sitka and the other in Wrangell. The act specified that the laws of the State of Oregon were, as far as applicable, to be in force in Alaska and proclaimed Alaska a land district. Mining claims were to be registered with the four commissioners. Until the Klondike gold rush in 1898 provided further incentive for additional federal legislation, the Organic Act of 1884 remained the basic instrument of government in the territory.

Along with the struggle to secure additional civil government in Alaska, the boundary dispute between Canada and the United States also became a major issue. The geographic basis of the resulting treaty was at best defective and over several decades caused persistent tensions between Canada/Britain and the United States. In 1903 the boundary dispute was resolved, largely in favor of the United States, which caused long-lasting Canadian resentment.

The Klondike bonanza in the Yukon Territory captured the attention and imagination of the world. The least arduous route to these gold fields lay up the Lynn Canal, and it was crucial to the Canadians to have direct control of the harbors. Americans strongly objected, and American customs were established at Skagway and Dyea, while the Canadians established similar offices at the end of passes just a few miles away. As a result of this stampede, Southeast enjoyed several years of prosperity as gold seekers once again used the territory for a jumping-off point.

From 1896 to 1900 several congressional committees worked on effective legislation for the territory. The first substantive legislation were the Transportation and Homestead Acts of 1898. Railways were freed from the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and homesteads were restricted to surveyed plots of 80 acres. In 1899 the Criminal Code was enacted. The Carter Bill of 1900 in part provided for the establishment of a civil code for Alaska and three judicial districts. Courts were established in Sitka and later moved to Juneau.

Civil government in Alaska was still considered inadequate in spite of the fact that Congress was making progress. In 1899 discontent peaked in Southeast, and a convention of delegates from Ketchikan, Douglas, Juneau, Sitka, and other Alaskan centers met in Skagway. They favored a territorial government for Alaska, and John G. Price was elected to lobby in Washington for territorial status. His efforts were not very productive, principally because the Carter Bill—designed to provide for more efficient administration of Alaska—was about to be passed. Many congressmen felt that the demand for greater representation emanated primarily from Southeasterners who wanted to dominate the rest of Alaska. It was not until the 59th Congress in 1906 that Alaska secured the right to elect one delegate to Congress who would merely serve as a source of information on Alaskan affairs.

In 1911 James Wickersham, a prominent jurist who was one of Alaska's most ardent home rule advocates, and then Alaska's congressional delegate, introduced a bill providing for an Alaskan territorial legislature. The bill encountered some resistance, but was enacted into law in August of 1912. While the bill did not provide full legislative authority, it was nonetheless a marked improvement over the Organic Act of 1884. At about the same time southeast Indians organized themselves in the Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Alaska Native Sisterhood. These two groups provided a forum for discussion and expression among Southeast's aboriginal inhabitants and remained a strong force in the Native movement.

The first legislature met in 1913 and worked diligently to secure full rights for Alaskans. Among its first acts was to enfranchise women, seven years before the federal government. It requested that Congress liberalize the land laws to encourage and promote settlement in Alaska; it petitioned Congress to end land reservations and withdrawals and to rescind some already made; it requested better and more roads and lower freight rates.

The years after 1912 were problematic for Southeast. By 1918 fisheries production peaked, and although there were booms in mining and forest production, it was evident by the 1920s that economic domination of the territory by Southeast would soon be threatened by developments to the north.

Several issues confronted the territory in succeeding years, not the least of which was the resolution of aboriginal claims to lands in Southeast. No reservations were set aside for the Indians in that region, except for the Tsimishian at Metlakatla, and no treaties had been negotiated with them. The entire question of rights to land and other resource areas was held in abeyance, although the Natives had long maintained that their rights to the land had not been breached by the Treaty of Cession. In 1935 the Tlingit and Haida people brought suit in the U.S. Court of Claims for compensation for "lands and other tribal or community rights." Claims were subsequently filed by a few Tlingit communities, but the court denied them. The question again came up as a result of a section of the Alaska Fisheries Regulations of 1942 that provided "no trap should be established in any site in which any Alaska Natives have any rights of fishery by virtue of any grant or of aboriginal occupancy."

The Department of Interior held hearings in Tlingit and Haida villages to determine "fishing and other occupancy rights of these communities." Individuals testified concerning their kinship groups and the areas they traditionally fished and located their camps, smokehouses, and other sites. Native claims to resource sites and lands were contested by canneries and other business interests, but the Court of Claims eventually awarded the Tlingit and Haida residents more than $7.5 million for lands withdrawn for the Tongass National Forest, the Annette Island Reserve, and the Glacier Bay National Monument. Also, the court found that "Indian Title" survived unextinguished to 2.6 additional acres of land in the area. However, final resolution of Native title to lands in Southeast was not definitively resolved until passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act on December 18, 1971.

In the intervening years Alaska's uniqueness and value to the nation had been proved. Her strategic geographic position became evident during World War II, a massive military construction boom followed, and the quest for statehood became a key issue.

As the final push of almost a half a century of dedicated, if somewhat sporadic effort, the statehood movement of the 1950s pulled together diverse and frequently conflicting interests and molded them into a common desire for increased self-government and local control over the territory's natural resources. A major product of this final effort—Alaska's constitutional convention—built upon the consensus and enthusiasm generated by the statehood cause, and in the process, rose to high levels of idealism and dedication. The result was a very successful and a widely supported state constitution (Fischer 1975).

Statehood was finally achieved in 1958. Southeast retained the capital in Juneau, and that city grew enormously as government services and ancillary industries established themselves there. Nonetheless, with the growth of cities on the northern gulf and Cook Inlet, the focus of economic and political power gradually began to shift out of the region.

Southeast is still important as the center of government services, although in 1974 an initiative was passed to move the capital from Juneau to an as yet undetermined site. The important wood processing and fishing industries still center in Southeast, and these in turn have encouraged the growth of important distributive industries. Southeast is still one of the most important economic and political sections of the state. The region's vast array of natural resources provided the basis for the beginnings of organized modern industry in the territory, and its Native and non-Native peoples have been foremost in the fight to effect a just settlement of the patrimony of all inhabitants of the state.

Figure 147

Important Dates and People in Alaska's History

|

Important Dates in Alaska's History |

||

|

October 18, 1867 |

Russian America transferred to the U.S. |

|

|

July 27, 1868 |

Customs Act passed; first bill relating to Alaska |

|

|

1877 |

U.S. Army troops withdrawn from Alaska |

|

|

August 1, 1879 |

"Provisional Government" established in Sitka |

|

|

August 16, 1881 |

First territorial convention, Harrisburg |

|

|

1884 |

The First Organic Act passed Congress |

|

|

October 8, 1890 |

Second territorial convention, Juneau |

|

|

1897 |

Start of the Klondike gold rush |

|

|

October 9, 1899 |

Criminal code for Alaska |

|

|

1900 |

Civil code for Alaska |

|

|

1900 |

Juneau becomes the capital of the territory |

|

|

1903 |

Alaska-Canada border defined |

|

|

1905 |

Legal status of Alaska as an incorporated territory defined by Supreme Court |

|

|

May 1906 |

Alaskan delegate bill passed |

|

|

August 24, 1912 |

Home Rule Act provided for a "territorial legislature" in Alaska |

|

|

1913 |

First territorial legislature |

|

|

1916 |

Delegate Wickersham introduced first statehood bill for Alaska in Congress |

|

|

1923 |

Pres. Harding drives last spike in federally owned Alaska Railroad |

|

|

1927 |

State flag adopted |

|

|

1955 |

Delegates to a statewide constitutional Convention elected |

|

|

1955-1956 |

Constitutional convention at the University of Alaska |

|

|

1956 |

Territorial voters adopt the constitution and send two senators, Ernest Gruening and William Egan, and one representative, Ralph Rivers, to Washington under the Tennessee Plan |

|

|

1958 |

Statehood Bill for Alaska signed by President Eisenhower |

|

|

1959 |

Statehood proclaimed |

|

|

1964 |

Great Alaska earthquake |

|

|

1969 |

Oil discovered in Prudhoe field |

|

|

1971 |

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act |

|

|

1974 |

Initiative to move state capital approved by electorate |

|

|

Governors in Chronological Order |

|

|

John H. Kinkead |

July 1884-May 1885 |

|

Alfred P. Swineford |

May 1885-April 1889 |

|

Lyman E. Knapp |

April 1889-June 1893 |

|

James Sheakley |

June 1893-June 1897 |

|

John G. Brady |

June 1897-March 1906 |

|

Wilford B. Hoggatt |

March 1906-May 1909 |

|

Walter E. Clark |

May 1909-April 1913 |

|

John F.A. Strong |

April 1913-April 1918 |

|

Thomas Riggs, Jr. |

April 1918-June 1921 |

|

Scott C. Bone |

June 1921-August 1925 |

|

George A. Parks |

June 1925-April 1933 |

|

John W. Troy |

April 1933-December 1939 |

|

Ernest Gruening |

December 1939-April 1953 |

|

B. Frank Heintzlemann |

April 1953-January 1957 |

|

Mike Stepovich |

April 1957-August 1958 |

|

William A. Egan |

January 1959-December 1966 |

|

Walter J. Hickel |

December 1966-January 1969 |

|

Keith H. Miller |

January 1969-December 1970 |

|

William A. Egan |

December 1970-November 1974 |

|

Jay S. Hammond |

December 1974- |

|

Lieutenant Governors |

|

|

Hugh Wade |

1959-1966 |

|

Keith Miller |

1966-1969 |

|

Robert W. Ward |

1969-1970 |

|

H.A. Boucher |

1970-1974 |

|

Lowell Thomas, Jr. |

1974- |

|

Delegates in Chronological Order |

|

|

Frank H. Waskey |

1906-1907 |

|

Thomas Cale |

1907-1909 |

|

James Wickersham |

1909-1917 |

|

Charles A. Sulzer |

1917 |

|

James Wickersham |

1918 |

|

Charles A. Sulzer |

1919 |

|

George Grigsby |

1919 |

|

James Wickersham |

1921 |

|

Dan A. Sutherland |

1921-1930 |

|

James Wickersham |

1931-1933 |

|

Anthony J. Dimond |

1933-1944 |

|

E. L. Bartlett |

1944-1958 |

|

Tennessee Plan Delegates |

|

|

Senators |

|

|

Ernest Gruening |

1956-1958 |

|

William A. Egan |

1956-1958 |

|

Representative |

|

|

Ralph Rivers |

1956-1958 |

|

Statehood |

|

|

Senators |

|

|

E.L. Bartlett |

1959-1968 |

|

Ernest Gruening |

1954-1968 |

|

Mike Gravel |

1968- |

|

Ted Stevens |

1968- |

|

Representatives |

|

|

Ralph Rivers |

1959-1966 |

|

Howard Pollock |

1966-1970 |

|

Nick Begich |

1970-1972 |

|

Don Young |

1973- |

|

| Chilkat dancers perform famous tribal dances at Port Chilkoot. |