|

Alaska

Native Land Claims

|

|

|

Unit

4 - The

Land Claims Struggle

|

|

|

Chapter

16 - Organization

|

|

Chapter 16

Organization

The number of regional Native organizations had grown to four with the founding of the Association of Village Council Presidents in southwest Alaska in 1962. In addition, one urban organization which had been established in 1960 — the Fairbanks Native Association — was holding regular meetings and addressing issues of concern to Natives. But each of the organizations was separated by great distances from the others, the cost of communication was high, and there was little contact among the groups.

|

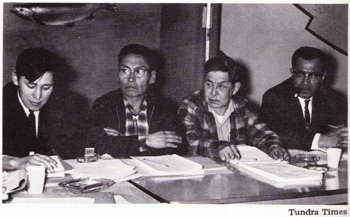

| William L. Paul, Sr., Alaska Native Brotherhood, and Al Ketzler, Tanana Chiefs conference, 1963. |

The first steps toward the development of a statewide organization were taken early in 1963, when leaders of several associations discussed the possibility of its formation. The proposal to unite the associations was made at a meeting of the Tanana Chiefs Conference by Steven V. Hotch, an officer of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. When Hotch called for an affiliation of the Dena Nena Henash and Inupiat Paitot with his organization, the idea was supported by his President Emeritus, William L. Paul, Sr., and by spokesmen for the other two groups. It appeared that the affiliation would be accomplished.

However, some leaders, such as State Senator Eben Hopson, of Barrow, feared there might be an imbalance of regional representation on whatever governing body was set up. Hopson was also concerned that the organization from southeastern Alaska would become the dominant force, overshadowing the other regions. In a letter to Tundra Times editor Howard Rock, he warned, "I can just picture you and a handful of other Eskimos sitting at a conference table with a full battery of the members of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, and being voted down on every proposal you might have."

Those who supported the idea of one statewide organization tried to persuade others, but they were unable to overcome a deeply rooted mistrust which many Natives had of people outside of their own geographic regions.

The task of overcoming mistrust became easier as Natives began to realize, in part through the Tundra Times, that they were facing a common threat of land loss. There was also increasing communication among Natives from different regions as they gathered together in government-sponsored advisory committees dealing with housing, health, or education programs.

|

| Board of Directors, Cook Inlet Native Association. Standing: Emil Notti, John Evans, Lloyd Ahvakana, Al Yakasoff, Flore Lekanof, Shirley Tucker, Carol Bahr, Dorothy Watson, Jim Claymore. Seated: Mike Alex, Laura Bergt, Fred Notti, and Don Watson. |

New organizations. In 1964 two new organizations of Natives were established: Gwitchya Gwitchin Ginkhye (Yukon Flats People Speak) made up of Yukon Flats villages, and the Cook Inlet Native Association, founded by residents of the state's largest city, Anchorage. In the same year, another attempt was made to unify the efforts of Native organizations.

This conference of Native organizations was planned by Rock, Al Ketzler, Ralph Perdue, the president of the Fairbanks Native Association, and Mardow Solomon, the president of the newly founded Gwitchya Gwitchin Ginkhye. The themes of the conference were the need for increased political activity among Natives and the need for cooperative action to achieve common goals. The grand president of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, John Hope of Sitka, chaired the two-day event. Although Roy Peratrovich of Juneau and others stressed the need to hold the conference annually, no further meeting of the group was to take place.

Two more years would pass before a statewide organization would be formed. And for most of that time, little new organization, even on a regional basis, would take place. The establishment of the Tlingit-Haida Central Council, headed by Andrew Hope of Sitka, was an exception. Unlike the other groups being formed in these years, it was not established to protect land rights threatened. Its purpose, instead, was to plan for the distribution of funds expected as a result of the 1959 court determination that southeastern Indians were owed compensation for lands taken.

Apart from a protest by the village of Tanacross against the sale of ancestral lands at George Lake, a protest which stopped the sale, claims to land created little public notice in 1965. There was, however; a growing awareness among villagers of threats to their land and steps they needed to take to protect their rights to it.

|

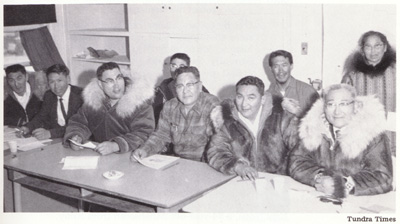

| Charles Edwardsen, Jr. of Barrow, Jacob Stalker of Kotze-bue, Axel Johnson of Emmonak, and Frank See of Hoonah at meeting of Alaska Native Housing Committee, 1966. |

Community organization. Broadening the land rights movement across the state was, in large measure, the achievement of "Operation Grassroots." This community organization effort, headed by Charles Edwardsen, Jr., of Barrow, was an arm of the Alaska State Community Action Program (ASCAP). This state-operated agency was a part of President Lyndon Johnson's antipoverty program funded by the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO).

Over the next few years, funding from OEO through ASCAP, and its successor, RurAL CAP, was to be a key factor in claims settlement work of regional Native organizations. Although the antipoverty funds were not targeted to the support of land claims, they were intended to support community and regional organizations, and planning toward the solution of shared problems. Many members of the antipoverty boards and their staffs were, therefore, actively involved in the claims struggle.

|

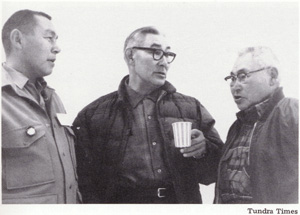

| (L to R) James Nageak, Abel Akpik, Samuel Simmonds, Walton Ahmaogak, Sam Taalak, Otthneil Oomituk, and Herman Rexford. (Man behind Ahmaogak and woman at right are not identified.) |

Arctic Slope claim. During 1965 national focus on problems of village housing, education, and poverty resulted in some overshadowing of Native claims. The subject of Native land rights, however, returned to public attention in early 1966 with the announcement by a new organization in Barrow, the Arctic Slope Native Association, that it was making claim to virtually all of the land north of the Brooks Range. A spokesman said the group was seeking full title to 58 million acres on the basis of aboriginal use and occupancy.

The new organization was established at a meeting called by Charles Edwardsen, Jr., to discuss land rights of Eskimos. It chose Sam Taalak of Barrow as its president.

In April of 1966, Senator Ernest Gruening pointed out that, because of Native protests against State selection, only three million acres of land had been transferred to the State. He complained that the Bureau of Indian Affairs had encouraged the filing of such protests and that the Interior Department, of which it was a part, was apparently making "every acre of Alaska subject to questionable claims of rights by Native protests." If there were valid rights, he argued, the Interior Department should propose legislation to allow cash compensation to be paid.

A 24-year-old Eskimo graduate student at the University of Alaska, Willie Hensley, was quick in his reply to the Senator. Hensley criticized Gruening for his failure to consult with Natives before "creating a prejudiced attitude toward them by his statements" and further, for ruling out any land as part of a settlement. He said, in part,

Compensation in cash would certainly be a simple and quick solution for Congress to buy off Native claims, but it seems we should be given an opportunity to voice our opinions on the matter . . .

|

| Nick Gray, founder of Native associations in Fairbanks, Anchorage, and Bethel |

The hopes of Native leaders for a unified organization persisted. What was perhaps the most eloquent plea was made by Nick Gray, a founder of the Native organizations in Fairbanks and Anchorage, and more recently, a founder of a Bethel area group, the Kuskokwim Valley Native Association. From his hospital bed, where he lay gravely ill, he wrote:

It is gratifying to observe the awakening of our people to the necessity of cooperative effort by forming associations, brotherhoods, . . . to protect our heritage . . .

Our hereditary claims can hardly be denied, since they extend far into the dim pages of history, for outdating the beginnings of most currently established nations . . . The next logical step for these separate and far-flung groups is affiliation and then eventual amalgamation into a harmonious whole department dedicated to achieve the most good for all.

What Gray envisioned — a statewide organization — was to be achieved shortly before he died.

|

| Emil Notti, first president of the Alaska Federation of Natives |

Statewide organization. The meeting which resulted in the establishment of what was to become today's Alaska Federation of Natives was called by the president of the Cook Inlet Native Association, Emil Notti, a 34-year-old Athabascan from Ruby.

In organizing the meeting, Notti had the assistance of Chief Albert Kaloa, Jr., of Tyonek village, Stanley J. McCutcheon, an attorney who had, helped Tyonek win almost $13 million from oil leases on its reserve, and Thomas Pillifant, an area superintendent for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Tyonek village provided most of the financing of the convention.

|

| Delegates to the first statewide Native conference. Dan Lisburne of Point Hope, Frank Degnana of Unalakleet, and Billy Beans of St. Mary's |

The historic meeting began on October 18, 1966 — on the ninety-ninth anniversary of the transfer of Alaska from Russia. Seventeen Native organizations were represented. The total attendance was estimated at 250 persons.

Notti presided over the three-day conference as it chose a board of directors, named committees, and began flexing its strength politically.

Land recommendations. Recommendations of the land claims committee, chaired by Willie Hensley, were unanimously approved by the conference. The three fundamental recommendations were that:

1) a "land freeze" be imposed on all federal lands until Native claims were resolved;

2) Congress enact legislation to enable settlement of the claims; and

3) there be substantial consultation with Natives, including Congressional hearings in Alaska, before any action would be taken on claims settlement legislation.

The conference also adopted specific recommendations for legislation. The proposed bill, the conference said, should authorize court action to settle claims for Native lands taken and award compensation at current market value. Further, it should award title to other lands which were valid[ly] claims.

|

| At left, Tyonek's attorney Stan McCutcheon of Anchorage, who helped organize the first statewide conference of Natives. At right, Willie Hensley of Kotzebue, Land Committee chairman and later a State Representative. |

Political importance. In addition to achieving a united stand regarding land claims, the meeting was important in identifying Natives as a significant political force. Delegates were astonished at the attention which they received from well-known political figures in the state. One Native leader in attendance at the convention observed that, if any delegate was seen paying for his own meal, it was probably because he chose to dine alone!

|

|

||||

|

|||||

The growing political importance of Natives was evidenced again in November when association leaders were elected to the legislature. The three elected to the State House were: A University of Alaska student who was president of the Tanana Chiefs, John Sackett; Jules Wright, president of the Fairbanks Native Association; and the founder of the Northwest Alaska Native Association, Willie Hensley of Kotzebue. Together with Carl E. Moses of Unalaska, Frank See of Hoonah, John Westdahl of St. Mary's — all in the House — and Ray Christiansen in the State Senate, Natives held seven of the sixty seats in the legislature.

To continue the work of the Alaska Federation of Native Associations, the name temporarily adopted for the statewide group, an Aleut from St. George, Flore Lekanof, was elected chairman. When the group met a second time (early in 1967), it emerged with a new name, The Alaska Federation of Natives, and a full-time president, Emil Notti.

| Alaska Native Land Claims Copyright 1976, 1978 by the Alaska Native Foundation |