A Bridge Between Two Worlds

the term half breed gets a new definition

by Brad Williams

photos by Jason Rand

"A Bridge Between Two Worlds," Brad Williams,

"True North," Spring 1999, p. 10-14. Used with permission of

the publisher, for educational purposes only. Note from the publisher:

The complete magazine is free, however, our press run was limited and

many have already been distributed to various locations statewide. Contact

distribution manager, Cynthia Deike-Sims: cynthiadeike@hotmail.com,

for any available hard copy issues.

|

Jack Dalton,

26, a writer and storyteller of half Yupíik Eskimo and half German descent,

recalls meeting his birth mother for the first time at age 22. "When I

went to Hooper Bay, [Alaska], my mom gave me a Yupíik name, CupíLuaraq. It means

little reed pipe. Then she told me a little story: ĎYou see, when we are walking

with the land and need to drink, we use little reed pipe. You see when we are

swimming with the water and need to breathe we use little reed pipe. You see,

little reed pipe is the bridge between two worlds. Jack, you are the bridge

between two worlds.í"

Jack Dalton,

26, a writer and storyteller of half Yupíik Eskimo and half German descent,

recalls meeting his birth mother for the first time at age 22. "When I

went to Hooper Bay, [Alaska], my mom gave me a Yupíik name, CupíLuaraq. It means

little reed pipe. Then she told me a little story: ĎYou see, when we are walking

with the land and need to drink, we use little reed pipe. You see when we are

swimming with the water and need to breathe we use little reed pipe. You see,

little reed pipe is the bridge between two worlds. Jack, you are the bridge

between two worlds.í"

Like many Alaska Natives of mixed lineage, Dalton faces the question of what

it means to be part Native in a modern, western society and still bridge the

gap between these two worlds.

Daltonís worlds first parted when he was only five days old. Flown from Bethel

to Anchorage, he was given up for adoption and raised by a non-Native family.

His parents told him about his adoption at age 5. This was the first time he

realized he was different from the rest of his family and others. He doesnít

recall having role models.

"Because I was adopted, I had this idea that I couldnít be like the people

I was surrounded by." He found himself in an identity crisis between what

it meant to be Native and what it meant to be white simultaneously. "Being

Native means constantly struggling to survive. Managing to do it and being happy

in spite of it," Dalton said. "I think there are very few people on

the earth good at being Native."

Tim Gilbert, 41, of Kotzebue takes pride in both his Inupiaq Eskimo and Metlakatla

Tsimshian Indian heritage. He struggled with identity as a result of being raised

by a non-Native adoptive family as well. "The burden of learning my Nativeness

was solely on me," he recalled.

Gilbert moved to Kotzebue to be closer to his birth fatherís family and assumed

a position as the local hospital administrator. "Part of my reason in coming

up here was to find out what it means to be Inupiaq," he said, and "to

be exposed to more traditional ways of the Inupiaq."

Gilbertís children are half Navajo Indian, one quarter Inupiaq Eskimo, and

one quarter Tsimshian Indian. He encourages them to learn about their heritage.

"I was always pressing them to learn more about their history," he

said.

Soon Gilbertís

children will have to choose their tribal connection in order to attain their

Certificate of Indian Blood. He said that one child is considering choosing

Navajo, while the other might decide to be registered tribally as Inupiaq.

Soon Gilbertís

children will have to choose their tribal connection in order to attain their

Certificate of Indian Blood. He said that one child is considering choosing

Navajo, while the other might decide to be registered tribally as Inupiaq.

The U.S. government allows tribes to determine oneís status as a member using

the method of blood quantums. Once the blood quantums have satisfied the tribeís

minimum requirement and been verified by a birth certificate, an applicant receives

a blood certificate from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Michael Jennings, head

of the Native Studies Department at the University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA),

points out the only four times in the history of the world blood quantum identification

has been required: "Black" Koreans in Japan, Jewish people in Nazi

Germany, South African Blacks and both Native Americans and Alaska Natives in

the United States. Jennings added, "The drive has been for 250 years to

assimilate Natives."

UAAís Associate Dean of Students and Professor of Anthropology, Kerry Feldman,

concurred that western people have been waiting for Native Americans to be assimilated

for hundreds of years. He feels assimilation, in this case, would mean completely

absorbing Native culture. However, he does not see that happening.

"Human beings have been mating on the borders for the past one and a

half million years," Feldman said. He points out that what is known as

race holds little merit from a biological standpoint. Variance in ethnicity

and genotypic differences make up humanity. "There are more similarities

in genes among humans than there are differences in ethnicities." He feels

that anthropologists in Alaska have not focused on this topic nearly enough.

Non-Natives have been mixing with Alaskaís Native population since the 18th

century. The Aleuts were the first to come into contact with foreigners. In

1743, Russian fur hunters, or promyshlenniki, made their mark on the far-reaching

Aleutian chain and its indigenous people. They forced the Aleut men to do the

hunting while the Russians dallied with the Aleut women. As a result, there

are almost no known full-blooded Aleut people remaining today. The Russians,

followed by the British, Spanish, French, Chinese, Scandinavians, Japanese and

Germans, further lowered the blood quantum levels among Alaska Natives.

Priscilla Hensley, 24, a UAA student and dance choreographer, contends with

being categorized in both daily life and on paper, "I hate those boxes

where you have to check off your ethnicity. Itís like you have to choose which

part of yourself you like best."

Hensley, daughter of Alaska Native activist, Willie Hensley, is Inupiaq Eskimo,

English, Irish, Scottish, French, and Lithuanian. As a little girl she had always

feared that the mixing of races would eventually result in everyone being gray.

Even now, she contemplates her "fear of gray." "I have some concern

that there will be this bleaching of things." She speaks of a type of "survivorís

guilt."

"I get the benefit of looking white. I feel like I should put a sign

on myself that says ĎLook! Iím Native too!í" She adds, "I donít disappear

into either world. Iím something else altogether. To not be accepted either

way makes us a third thing."

This "third thing," the question of identity, comes up for many children

of mixed bloodlines.

The U.S. Census Bureau is also struggling with racial labels and how they

will apply to multiracial Americans on the national census in 2000. The Advisory

Board for the Effect on Multiracial Self-classification and Census 2000 recognizes

that inevitable changes will occur in the meaning of race and racial groups.

They are not finding any easy metaphors or key slogans to describe what America

is becoming.

The metaphors of a "melting pot" and "mosaic" fall short

given what is known today. The melting pot suggests a loss of identity, and

mosaic suggests that people will never come together, but rather maintain a

rigid separation.

Instead, according

to the Census Advisory Board, America is becoming a new society based on a fresh

mixture of immigrants, racial groups, religions and cultures, in search of a

new language of diversity that is inclusive and will build trust. There is no

simple way to say what race or racial groupings mean in America, because they

mean very different things to those who are either in or out of the target "racial"

group.

Instead, according

to the Census Advisory Board, America is becoming a new society based on a fresh

mixture of immigrants, racial groups, religions and cultures, in search of a

new language of diversity that is inclusive and will build trust. There is no

simple way to say what race or racial groupings mean in America, because they

mean very different things to those who are either in or out of the target "racial"

group.

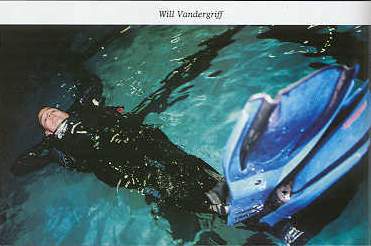

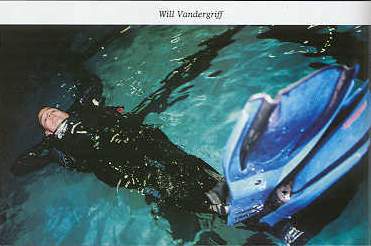

Will Vandergriff, 20, is a UAA broadcasting major who is half Inupiaq Eskimo,

part Dutch, and part Cherokee Indian. He has strong feelings about identity

and where the race line is drawn. "When I think of Alaska Natives, I think

of angst.

They tell me Iím anti-Native. They tell me I donít appreciate my Nativeness.

They say Iím too white. When they see me, they donít see an Alaska Native,"

said Vandergriff.

However, Vandergriff has seen both sides. Once, while on tour with an under-17,

all-star, national baseball team, a fellow teammate told him, "We donít

want anything that isnít 100 percent white American. So, you can take your fat,

lazy, Eskimo ass home."

His first memory of identifying himself as Eskimo was in eighth grade at the

Native Expo at West High in Anchorage, where he did wood carving. "It was

weird because they were talking in tongue and I couldnít understand. I was there

for seven hours."

Growing up in Anchorage, Vandergriff has had few opportunities to learn the

traditions of his ancestry. His mother invites him to her home to partake of

traditional foods and ways. "Thereís always lots of fish every time we

go to her house. She makes me mukluks [hand-made Eskimo boots]," he said.

Vandergriff learned how to seal hunt with his uncle, but regards traditional

ways with little value, "Thatís all well and good, but thatís not going

to get me a job in the real world. Tradition is important, but you canít base

your life on it."

Synette Underwood,

26, is part Athabaskan and part Irish. She fishes commercially with her family

in Bristol Bay every summer. She recalls an acquaintance incorrectly assuming,

"You carry on the Native traditions. You fish." But Athabaskans have

traditionally been caribou herders, and their fishing has been strictly river

dip netting, not gill net fishing.

Synette Underwood,

26, is part Athabaskan and part Irish. She fishes commercially with her family

in Bristol Bay every summer. She recalls an acquaintance incorrectly assuming,

"You carry on the Native traditions. You fish." But Athabaskans have

traditionally been caribou herders, and their fishing has been strictly river

dip netting, not gill net fishing.

Her family has been commercial fishing for more than 50 years. But it has

little to do with traditional Native ways and more with to do economics. Underwood

feels there is a convergence taking place. "You donít compromise one tradition

for the other. Youíre taking the best of both."

If taking the best of both is the key, then Phillip Blanchett, 24, is a harbinger

of things to come. Blanchett grew up in Bethel with his mother, a Yupíik Eskimo,

and his father, an African American. "I felt so honored to be a part of

both backgroundsí heritage," he said. He never felt the need to make a

choice between the two. "Iíve always marked myself on applications as black

and Alaska Native."

He recalls a time in his childhood when he originally noticed a difference,

"The first memory I have of being aware that I was African American was

when I noticed my hair was different," he said while grinning and holding

his hands above his head. "It was a big afro. None of the other Eskimo

kids had hair like that."

As different as Eskimo and African-American may seem, Blanchett believes there

is much more of a common bond which lies therein. At age 14, his family moved

to Anchorage and he found himself wondering how other kids at his new school

would think of him. Fortunately, his concerns were unwarranted, "My first

day at Bartlett [High School], I felt so accepted by the black community."

Also welcomed

by the Native community, he attended cultural events such as the Native Olympics

and the Arctic Winter Games. "I felt I could be myself when I was around

the Native community," he said. Blanchettís identity issues did not arise

as complications, but rather as affirmations. "I always felt like I had

something that no one could take away from me," he said. "I always

felt blessed."

Also welcomed

by the Native community, he attended cultural events such as the Native Olympics

and the Arctic Winter Games. "I felt I could be myself when I was around

the Native community," he said. Blanchettís identity issues did not arise

as complications, but rather as affirmations. "I always felt like I had

something that no one could take away from me," he said. "I always

felt blessed."

This sense of identity was instilled by both sides of his family. His father,

David Blanchett, grew up in Philadelphiaís inner city and never let him forget

who he was, "Youíre a Blanchett," he would always say, encouraging

pride in his son. "Every time you write your name, write out your full

name."

That attitude has taken Blanchett far. In fact, it took him to Greenland and

back, where his wife Karina is from. Karina, Phillip, his brother Stephen, and

their cousin Ossie Kairaiuak formed the group Pamyua [BUM-yo-ah]. Pamyua blends

traditional Inuit and Yupíik Eskimo song and dance with gospel, jazz and a touch

of what Blanchett calls "MTV, break dancing, hip-hop and KGOT [radio]."

Also known as Afro-Yupíik music, their style is as original as their backgrounds.

As a child, he watched his mother perform traditional Yupíik dances and thought

about how he would perform if he were dancing. Now heís doing just that. "Diversity

is what we bring to the performance; diversity, and then think further,"

Blanchett said. This convergence of traditional format combined with a contemporary

style is how Pamyua manifest their own unique expression of cultural fusion.

Wanda Conley, 31, a half Inupiaq Eskimo and half Irish UAA student, participates

in traditional ways such as Native drumming and ivory carving. But she feels

Native traditions are not always the best approach. "They [Natives] are

fighting so hard to keep their identity, they are pushing out what can be gained.

We like what the white culture can give us, but we are trying to keep the old."

Conley has literally lived in both worlds. And it hasnít always been pleasant.

While living at Pt. Hope, above Alaskaís Arctic Circle, she experienced another

side of being multiracial. "I was treated badly by the Natives. Then when

I moved to Anchorage, I was treated badly by the whites." Prejudice works

both ways, as Tim Schuerch, 33, a part Inupiaq, part European mix, knows all

too well. Growing up between Kiana and Kotzebue, Schuerch has also dealt with

discrimination. Natives always perceived him as white. "I remember being

beat up in school because I was Ďwhite," he said. "Kids would tease

me by stealing my hat or my scarf." However, he did not always stand alone.

"There were also kids who had a sense of justice." Schuerch recognizes

justice. He holds a jurist doctor and recently passed the bar examination. After

graduating from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, he returned

to Alaska to apply for a job at Maniilaq Corporation in Kotzebue. "I applied

as a Native at Maniilaq because I understand the politics," he said. "I

wanted them to look at my application and say ĎHeís one of us.í" He currently

holds the position of special assistant to the president of Maniilaq.

He light-heartedly refers to himself as a "half-breed street rat"

and takes little credence in its original meaning. "Itís hard for me to

take umbrage at the term half-breed," said Schuerch.

One of MTVís "The Real World" Boston finalists, Cana Welm, considers

the label half-breed, in reference to her mixed lineage of Inupiaq Eskimo and

German, to be a "very precise term."

Welm recalls her tryout for "The Real World" and how people made

assumptions about her based on her looks and ethnicity. "When I was in

California, I was Alaska Cana," she said. "I was Eskimo-girl."

As with most mixed marriages, her parents came from very different backgrounds.

"My mom was born on a caribou mat and my dad was born in a castle in Germany."

Born and raised mostly in Kotzebue, Welm spent her junior high and college years

in Berkeley, Calif. Now living in Kotzebue again, she feels that peopleís stereotypes

and assumptions about her have reversed. "Iíve seen the extremes on both

sides," she said. "You donít want to be seen as an outsider when you

live here."

Outsider opposed to Native. White versus Eskimo. Modern eliminating tradition.

Blood quantums and heritage. These controversies all beg the question, "What

does it mean to be Native?"

Being Native is a perception. Being Native is an identity. Being Native is

where you are from. Being Native is who you are. But being multiracial in Alaska

today questions all these statements and more.

Jack Dalton attempts to address the question: "Thereís this idea that

being Native means you are closer to nature and somehow more spiritual."

However, for people of mixed lineage, "being Native" is not quite

so simple. "The Native part of themselves has more to do with their outlook

on life," he adds. "When you come right down to it, labels cannot

define you." He feels that applications corner him into being something

he does not relate to. "Otherí is not a race," Dalton said.

When people

ask what it is like being bi-racial, Dalton tells them that it is like having

two people living inside of him at the same time. "One is the Eskimo elder,

who is humble and wise with a lot of important things to say. The other is the

proud German who demands that I go out there to say those things." he said.

When people

ask what it is like being bi-racial, Dalton tells them that it is like having

two people living inside of him at the same time. "One is the Eskimo elder,

who is humble and wise with a lot of important things to say. The other is the

proud German who demands that I go out there to say those things." he said.

"Because Iím a half-breed, people think I would have less of an idea

of where Iím from," he said. These "two sides" have not always

agreed upon everything, but Dalton has found his own answer. "You can either

take the good of both and make yourself a better person. Or you can take the

worst of both and be self destructive."

As with many Natives of multiracial backgrounds, Dalton has wrestled with

his identity as well as how others perceive him. Although for Dalton, who has

bridged that gap, the struggle has come to an end. "I identify myself as

Jack Dalton and when I have time," he said, " I tell them a really

neat story."

[Alaskool

Home]

Jack Dalton,

26, a writer and storyteller of half Yupíik Eskimo and half German descent,

recalls meeting his birth mother for the first time at age 22. "When I

went to Hooper Bay, [Alaska], my mom gave me a Yupíik name, CupíLuaraq. It means

little reed pipe. Then she told me a little story: ĎYou see, when we are walking

with the land and need to drink, we use little reed pipe. You see when we are

swimming with the water and need to breathe we use little reed pipe. You see,

little reed pipe is the bridge between two worlds. Jack, you are the bridge

between two worlds.í"

Jack Dalton,

26, a writer and storyteller of half Yupíik Eskimo and half German descent,

recalls meeting his birth mother for the first time at age 22. "When I

went to Hooper Bay, [Alaska], my mom gave me a Yupíik name, CupíLuaraq. It means

little reed pipe. Then she told me a little story: ĎYou see, when we are walking

with the land and need to drink, we use little reed pipe. You see when we are

swimming with the water and need to breathe we use little reed pipe. You see,

little reed pipe is the bridge between two worlds. Jack, you are the bridge

between two worlds.í"  Soon Gilbertís

children will have to choose their tribal connection in order to attain their

Certificate of Indian Blood. He said that one child is considering choosing

Navajo, while the other might decide to be registered tribally as Inupiaq.

Soon Gilbertís

children will have to choose their tribal connection in order to attain their

Certificate of Indian Blood. He said that one child is considering choosing

Navajo, while the other might decide to be registered tribally as Inupiaq.

Instead, according

to the Census Advisory Board, America is becoming a new society based on a fresh

mixture of immigrants, racial groups, religions and cultures, in search of a

new language of diversity that is inclusive and will build trust. There is no

simple way to say what race or racial groupings mean in America, because they

mean very different things to those who are either in or out of the target "racial"

group.

Instead, according

to the Census Advisory Board, America is becoming a new society based on a fresh

mixture of immigrants, racial groups, religions and cultures, in search of a

new language of diversity that is inclusive and will build trust. There is no

simple way to say what race or racial groupings mean in America, because they

mean very different things to those who are either in or out of the target "racial"

group.

Synette Underwood,

26, is part Athabaskan and part Irish. She fishes commercially with her family

in Bristol Bay every summer. She recalls an acquaintance incorrectly assuming,

"You carry on the Native traditions. You fish." But Athabaskans have

traditionally been caribou herders, and their fishing has been strictly river

dip netting, not gill net fishing.

Synette Underwood,

26, is part Athabaskan and part Irish. She fishes commercially with her family

in Bristol Bay every summer. She recalls an acquaintance incorrectly assuming,

"You carry on the Native traditions. You fish." But Athabaskans have

traditionally been caribou herders, and their fishing has been strictly river

dip netting, not gill net fishing.

Also welcomed

by the Native community, he attended cultural events such as the Native Olympics

and the Arctic Winter Games. "I felt I could be myself when I was around

the Native community," he said. Blanchettís identity issues did not arise

as complications, but rather as affirmations. "I always felt like I had

something that no one could take away from me," he said. "I always

felt blessed."

Also welcomed

by the Native community, he attended cultural events such as the Native Olympics

and the Arctic Winter Games. "I felt I could be myself when I was around

the Native community," he said. Blanchettís identity issues did not arise

as complications, but rather as affirmations. "I always felt like I had

something that no one could take away from me," he said. "I always

felt blessed."

When people

ask what it is like being bi-racial, Dalton tells them that it is like having

two people living inside of him at the same time. "One is the Eskimo elder,

who is humble and wise with a lot of important things to say. The other is the

proud German who demands that I go out there to say those things." he said.

When people

ask what it is like being bi-racial, Dalton tells them that it is like having

two people living inside of him at the same time. "One is the Eskimo elder,

who is humble and wise with a lot of important things to say. The other is the

proud German who demands that I go out there to say those things." he said.